Dilemmas and Challenges for the Amazon Biome

Submission received:

26 November 2024

/

Accepted:

8 December 2024

/ Published:

30 December 2024

Abstract

The Amazon represents a socio-environmental complexity whose resolution of the tensions that exist necessarily involves multilateral actions. Its biome is shared by several countries that have different standards regarding this relationship with nature. On the other hand, internal actions in each country, from the border, through the urban network and the implementation of infrastructure, pose challenges for governments to meet the population’s desires without intensely affecting the Amazonian environment. Thus, one of the paths has been the expansion of protected areas and territories, and the creation of Indigenous lands or reserves as a way of ensuring the conservation of forests and the way of life of traditional populations way of life that have a harmonious relationship with nature, counting, for this, with the financial support of Northern countries. They also have a strong interest in environmental conservation in the face of advances in livestock farming, monoculture, and extreme climate changes.

Article

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this article is to present an overview of the Pan-Amazon from two perspectives centered on the dilemmas and challenges faced by the region. We must consider its large border, which covers nine countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela, and French Guiana. These countries share the largest area of tropical forest in the world. Consequently, they bear a significant responsibility for the global environmental fate, as well for Indigenous peoples and natural resources (NOGUEIRA, 2007).

The Amazon is an extensive and complex biome, and its delimitation is particularly challenging due to the various criteria that can be used to define it. According to Nogueira (2007), excluding French Guiana, since it is not an effective part of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACTO), is already sufficient to alter the statistics. In Brazil, the inclusion or exclusion of the western region of the state of Maranhão also has a significant impact. In Venezuela, some authors propose including part of the Orinoco River basin. These boundaries are established and adjusted by conventions, often influenced by political interests. This leads to misalignment in terms of extent and population, resulting in a different definition of the Amazon depending on the criteria used.

Regarding the hydrographic region, the Amazon covers 6,925,674 km². In Brazil alone, it spans 3,869,953 km², occupying 42% of the national surface. It encompasses multiple countries from its sources in the Peruvian Andes to the Atlantic Ocean north of Brazil, covering the territories of Brazil (63%), Peru (17%), Bolivia (11%), Colombia (5.8%), Ecuador (2.2%), Venezuela (0.8%), and Guyana (0.2%). There are 294 municipalities within the Amazon domain, with notable capitals including Manaus (AM), Rio Branco (AC), Porto Velho (RO), Boa Vista (RR), Macapá (AP) (BRASIL DAS ÁGUAS, 2023).

With its largest portion in Brazilian territory, the influence and importance of cities are highlighted, particularly Manaus (AM), noted as the city with the largest population in the Western Amazon, followed by Belém (PA) in the Eastern Amazon. The regional capitals serve as significant nodes in circulation networks, facilitating exchanges and flows that extend beyond the Amazon region. In this context, it is important to highlight that the historical process of occupation and formation of the circulation network in the Amazon has unfolded in diverse ways. This process explains the demographic concentrations, regional nodes, and articulations that exist, underscoring changes that have occurred over the decades, as noted by Corrêa (1987) and Tavares (2011). This composition of the urban network occurs in a dispersed yet concentrated manner-dispersed in terms of the distances between urban centers, and concentrated in that a large portion of the population is concentrated in a few urban centers. This paradigm is historically constructed but remains more pronounced in the Western Amazon, characterized by less presence of road networks and a greater influence of the hydrographic network (LIMA, 2014; BERNARDINO et al., 2023).

The Amazon region exhibits a diverse population, characterized by a variety of social groups including riverside communities, Indigenous peoples, rubber tappers, extractors, quilombolas, urban groups, and migrants who reside along rivers and highways. There is a notable concentration of these groups in urban spaces, as emphasized by surveys conducted by IBGE (2022).

It is crucial to consider urban populations, exemplified by the city of Manaus with its 2,063,689 inhabitants, who comprise more than half of the total population of the state of Amazonas, the largest state in Brazil with 3,941,613 inhabitants according to IBGE (2022). With demographic growth comes an increased demand for services, infrastructure, and connectivity between places. These modern societal demands often drive conflicts and lead to territorial tensions. Connectivity with fixed objects and the flows they generate can cause clashes among the diverse social groups inhabiting the Amazon region. It is important to note that while the Amazon includes specific areas with low population density, it is occupied, and its territories are delimited by those who live on rivers, floodplains, and land. However, the elements used for habitation differ significantly from those typically found in urban settings1.

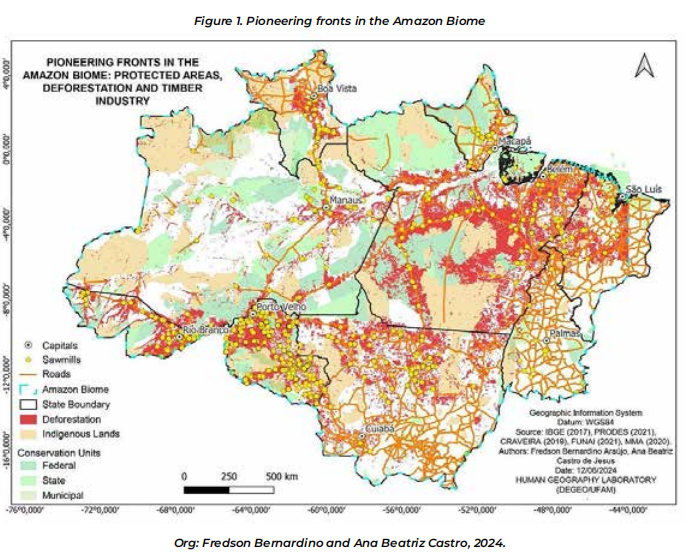

In the contemporary period, conflicts, and tensions in the territorial area of the Amazon are primarily concentrated in the southern portion of the state. Here, ongoing transformations driven by the advance of pioneering settlement fronts focused on space appropriation for production or land speculation, are particularly notable. These dynamics characterize the changes occurring within this pioneering frontier (CASTRO DE JESUS et al., 2023a; OLIVEIRA NETO, 2024). One indicator of pioneering fronts in the Amazon is the presence of legal or illegal corporations engaged in logging and processing wood from the Amazon rainforest.

Craveira and Bernardino (2024) highlight that within the dynamic of active pioneer fronts, Conservation Units (UC) and Indigenous Lands (TI) are prominent. These areas face increasing pressure from deforestation processes, illustrating aspects of territorial tensions that make it possible to understand the ongoing process of pioneer fronts in the region (Fig. 1).

It is important to note that the establishment of protected areas and Indigenous lands as measures to combat deforestation has formed mosaics of protected territories, primarily instituted by the State, including federal and state governments (NOGUEIRA; OLIVEIRA NETO, 2017). However, even inhabitants of ILs cannot consider their way of life fully protected, as they face pressure from deforestation. The Karipuna, for instance, Indigenous land2 has already experienced significant territory loss due to deforestation along its edges (CRAVEIRA and BERNARDINO, 2024).

It is worth noting that monitoring in the Amazon region poses significant challenges, exacerbated by pressures such as land grabbing, invasions, land regularization, and mining. These issues are particularly prevalent in areas with high intensity of pioneering fronts, such as Southern Amazonas (REZERA, 2005; SILVA et al., 2021). Therefore, besides considering natural resources, one must not overlook the existing occupation prior to the implementation of “large projects” aimed at infrastructure development.

1 On this issue, see the text by Cruz (2007) on the territorialities of fishermen on the Solimões River and the fishing territory (haul).

2 Karipuna Indigenous Land (TIKA), located in the municipalities of Porto Velho and Nova Mamoré, in Rondônia (RO).

AMAZONIAN BORDER ARCH

According to Foucher (1991), the establishment of borders between national states is primarily mediated through factors such as negotiation between countries, arbitration by a third party, imposition through military occupation or settlement by population, and through war where territory may be appropriated by the victorious country. On the other hand, the forms of border interaction present different typologies, as classified by Cuisier-Raynal (2001): Margin, characterized by national dominance; Buffer Zone, where tensions, military presence, or settlement challenges exist; Fronts, involving military or civil occupation processes; Capillary, characterized by spontaneous, local interactions without direct involvement from the respective countries; Synapse, marked by extensive border interaction, often supported by bilateral agreements to foster this dynamic.

Brazil has a border extending over 15,000 kilometers including the border with the Overseas Department of French Guiana, an exclusive space between Brazil and the European Union. The Amazon portion of Brazil’s border stretches approximately 10,000 kilometers, beginning at the Oiapoque River on the border with French Guiana and tracing the perimeter of the Amazon rainforest to the southern tip of the state of Rondônia. This dividing line was established in different periods of Brazilian history: colonial (1500-1822), imperial (1822-1889) and republican (1889-present).

The border with French Guiana, spanning 730 kilometers, was defined during the republican period through arbitration conducted by the Republic of Switzerland, with the Oiapoque River established as the basis for delineation. There are two cities: Oiapoque (Brazil), with 27,000 inhabitants, and Saint Georges de l’Oyapoque, with 5,000 inhabitants, which exhibit a dynamic of integration facilitated by the international bridge, despite strict controls on the entry of Brazilian citizens. In this area, frequent surveillance is conducted to prevent illegal gold mining by Brazilian miners in the rivers of the region, highlighted by Wanderley (2019).

The border with Venezuela, spanning 1,495 kilometers, was established during the Brazilian imperial period through negotiations between the two countries (Lia Machado, 1989). Along this border, there is a Brazilian city named Pacaraima, with a population of 20,000, and another Venezuelan city named Santa Elena de Uairén, with approximately 30,000 inhabitants. These cities are located approximately 15 kilometers apart, but there is a frequent and complementary commercial dynamic between their inhabitants, who trade various products with each other. This border experienced a significant humanitarian crisis when a large influx of migrants from Venezuela sought refuge in Brazil starting from 2015, making it the primary escape route for Venezuelans. Between 2015 and 2019, Brazil received approximately 178,000 applications for asylum or temporary residence, according to UNHCR.

The border with Colombia spans 1,644 kilometers and was defined through negotiations between the countries during the republican period. Along this entire border, there are at least three points where populations from both countries interact: La Pedrera (Colombia) and Vila Bittencourt (Brazil), Tarapacá (Colombia) and Ipiranga (Brazil). These are small communities primarily occupied by military forces, equipped with military airports for defense and territorial control operations. The final point of contact is one of the most dynamic along the Amazon rainforest border, encompassing the cities of Tabatinga (Brazil), with approximately 66,000 inhabitants, and Leticia (Colombia), with 50,000 inhabitants. Both cities have distinct infrastructures supporting their respective national states, including large airports, ports, federal agency offices, bank branches, hospitals, universities, and a robust border trade dynamic. They are integrated into the same urban network with coordinated public transport systems.

The Javari River is the main border line between Brazil and Peru. There are approximately 1,000 kilometers separating the countries in a region where the main border contact point is between the cities of Benjamin Constant (Brazil), with 44,000 inhabitants, and Islandia (Peru), with 5,000 inhabitants, both located at the mouth of the river. From the mouth to the upper course of the river, the region is inhabited by populations of various ethnicities. From the source of the Javari River to the end of the border line, there are another 1,300 kilometers, encompassing the State of Acre, totaling 2,300 kilometers negotiated during the Brazilian imperial period. In this state, there are points of contact between cities such as Assis Brasil (Brazil), with 10,000 inhabitants, and Iñapari (Peru), with 4,000 inhabitants. This border serves as Brazil’s starting point for connectivity with the Pacific Ocean via a highway that extends to the port of Ilo, Peru.

The consolidation of Brazil’s border with Bolivia, spanning 3,120 kilometers, occurred in several stages: during the colonial period, approximately 1,400 kilometers along the Guaporé and Mamoré rivers were negotiated between Portugal and Spain; in the imperial period, approximately 1,120 kilometers were defined in the southern portion; the final segment of about 600 kilometers along the border with the state of Acre was negotiated during the rubber exploration period, when thousands of Brazilian migrants occupied Bolivian territories for rubber extraction.

It is important to note that along these 10,000 kilometers of border in the Amazon region, there are dozens of indigenous ethnic groups that are present on both sides of the border, as their territories already existed before the National States. They are the Waiãpi, the Yanomami, the Tukano, the Dessana, the Tikuna, the Marubo, the Ashaninka and other peoples, who live off the forest, fishing, hunting, and suffer constant threats of invasion of their lands by timber, fish, gold traders or cattle ranchers.

INFRASTRUCTURE IN THE AMAZON

The projects installed in the Amazon during the 1970s were called “large projects” due to their characteristic of requiring a fixed amount of capital in the order of billions of dollars, extra-regional recruitment of thousands of workers, creating their own city to house the employees , called company-town, move millions of cubic meters of land, whether in the extraction of minerals or in the construction of hydroelectric plants, in short, they mobilize a huge amount of inputs and require high-capacity means of transport.

The ideology driving all territorial policies for the Amazon until the late 1980s was rooted in nationalism, national security, and integration—a classic geopolitical approach. This ideology prioritized the construction of massive highways to connect the region to the country’s core, often overlooking economic goals and flow density. The aim was to establish the Brazilian State’s presence in the country’s remote areas, with transportation routes serving as the primary means to achieve physical integration. Another spatial strategy implemented was the initiation of numerous colonization projects, which encouraged thousands of people to migrate to the Amazon region to settle and cultivate the land. Defense support also expanded with

the creation of military commands, brigades, and platoons, altering local dynamics wherever they were established. In addition to stimulating the exploitation of all possible natural resources: soil, subsoil, and rivers.

In the 1990s, two instruments were created by the Brazilian State aimed at establishing the protection and surveillance of the Amazon territory based on a technological monitoring system called the Amazon Protection System and the Amazon Surveillance System – Sipam/Sivam3. Through these mechanisms, the Brazilian government controls the illegal exploitation of wood and ores, supported by personnel with technical qualifications to interpret satellite images, manage transmission mechanisms, and provide immediate information to the command

center.

Hydroelectric plants, beyond their basic energy-generating function, involve sophisticated technical aspects related to civil construction and the entire operation of energy generation control. This includes turbines, computational and transmission systems, and extensive networks of towers. These plants serve large energy-consuming agglomerations, and major cities, and integrate into the national electrical system, supplying energy to densely populated regions. Manaus and Boa Vista4, historically dependent on thermoelectric generation, now receive energy from Tucuruí via a transmission line over two thousand kilometers long.

The most notable geographic objects of the early 21st century, whose territorial dimension is expressed in the form of protected areas of the Amazon, such as Conservation Units, Extractive Reserves, Quilombola Territories, and Indigenous Lands. Until the mid-1980s, the number of areas created throughout the 20th century, destined for conservation units, totaled just over 124 thousand km² and in the last twenty-five years this value reached 619 thousand km², an exponential growth. Despite this, impasses and tensions are created with these new territorial cuts imposed by the Federal and State governments in areas of several municipalities, causing a debate on the management of these territories at the municipal level

(Nogueira, Oliveira Neto, 2017).

3 Amazon Protection System/Amazon Surveillance System; Available in: https://tinyurl.com/2vbn5fzb; accessed on July 25, 2024.

4 Expected completion of the energy network between Manaus and Boa Vista in 2018; Available in: https://tinyurl.com/2ksx3fkv, accessed on July 25, 2024.

THE AMAZON: ENVIROMENTAL POLICIES AND CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES ON EXTREME EVENTS

The Amazon is recognized as the world’s largest tropical forest, playing a significant role in Brazilian environmental policies, albeit amidst controversy. Since the economic cycles from rubber exploitation in the late nineteenth century to modern commodity production by agribusiness and widespread neo-extractivism, concern for preserving the Amazon gained international prominence in the 1970s. This was spurred by the construction of the Transamazonian Highway and colonization projects that led to high rates of deforestation, often supported by significant financing from the World Bank (HÉBETTE, 2004; CASTRO, 2007; PORTO-GONÇALVES, 2017).

In the 1980s, to address the environmental impacts of the region’s development, an agreement was reached with the World Bank leading to the establishment of the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). This marked a governmental initiative to improve the management of the Amazon’s natural resources. The Pilot Program for the Protection of Tropical Forests in Brazil (PPG7) was initiated in 1992, coinciding with the ECO-92 conference, emphasizing conservationist themes from its outset. It is a pioneering initiative that relied on international funding to promote sustainable development in the region (MELLO, 2006; BORGES, 2012; BORGES 2018).

Since the 2000s, the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm)5 has successfully reduced deforestation rates in the region. However, environmental policies in the Amazon have always grappled with the challenge of balancing conservation with economic development (Mello, 2006). In recent years, the relaxation of environmental standards and reduced inspection have contributed to increased deforestation and fires in this biome (CAPOBIANCO, 2017; SILVA, 2023).

5 More information can be obtained at http://combateaodesmatamento.mma.gov.br/, accessed on July 25, 2024.

EXTREME EVENTS AND THE PAN-AMAZON

Extreme weather events have become more frequent and intense in the Pan-Amazon region, impacting biodiversity, local communities, urban and rural populations, and the economies of the countries that share this rainforest. Other extreme phenomena such as droughts, heavy precipitation, floods, and tidal changes pose various challenges for the populations in the region, underscoring the vulnerability of social groups to climate change.

The Pan-Amazon, spanning nine countries in South America, plays a crucial role in regulating the hydrological cycle and absorbing carbon dioxide in this region of the planet. However, deforestation and environmental degradation compromise this capacity, exacerbating the impacts of extreme events. Prolonged droughts, for example, reduce river levels, affecting navigation, fishing, and water supplies. Floods, on the other hand, lead to landslides, infrastructure destruction, substantial agricultural losses, and hinder land transportation in remote areas, affecting the supply of entire cities.

Forest fires, often triggered by deforestation and unsustainable agricultural practices, have devastated extensive forested areas, releasing significant amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, and exacerbating global warming. Managing these extreme events requires an integrated and collaborative approach among Amazonian countries, focusing policies that promote climate resilience, environmental conservation, and sustainable development. In this context, it is noteworthy that the fragility of environmental policies, coupled with the progress of economic dynamics in the region, has led to extensive transformation of the forest, inflicting damage on local and regional ecosystems, as well as the populations that

depend on the cycles of forests and rivers for their subsistence (NEPSTAD, 1999).

THE AMAZON FUND AS A TROPICAL FOREST CONSERVATION POLICY

The Amazon Fund6 is a crucial initiative for the conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Established by the Brazilian government in August 1st 2008 (Decree No. 6.527), as part of Brazil’s commitment to preserving the Amazon and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, in a new round of bilateral agreements with various institutions, with a resource managed by the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES), by receiving voluntary donations from governments, institutions and companies, both national and international. Its main goal is to finance projects that combat deforestation and promote sustainability in the Amazon region.

The main objectives of the Amazon Fund are: i) reduction of deforestation; ii) conservation and sustainable use of forests; iii) institutional strengthening. The sources of funding are donations from foreign governments, especially Norway and Germany. These countries have been the largest contributors, recognizing the global importance of the Amazon in climate regulation and biodiversity. Brazil’s state-owned mixed-economy oil exploration company, Petrobrás, also made donations to the Fund.

Created to address complex environmental problems affecting the Amazon, this policy has become one of the main financing tools for conservation and sustainable development projects in the region, supporting initiatives aimed at reducing deforestation, strengthening local communities, promoting sustainable productive activities, and improving environmental management.

The management of the Amazon Fund has been the subject of political and institutional disputes. Since its creation, the fund has been administered by BNDES, with strategic guidance from the Amazon Fund Steering Committee (COFA). However, tensions arose in 2019, when the Brazilian government, under the administration of Jair Bolsonaro, proposed changes to the governance of this funding, including greater influence by the federal government in the allocation of resources7. These proposals raised concerns among the main donors, Norway

and Germany, which suspended their contributions, citing increased deforestation and a lack of transparency in the management of resources. The disputes reflect a broader dilemma between environmental preservation and economic development, exacerbated by policies that favor agricultural expansion and mineral exploration in the Amazon.

6 More information can be obtained at https://www.fundoamazonia.gov.br/pt/home/, accessed on July 25, 2024.

7 Information available in the article: https://tinyurl.com/zh5cf9cu. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

THE MAIN PUBLIC POLICIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL LAWS OF THE PAN-AMAZON COUNTRIES

The Pan-Amazon region encompasses countries that have their own environmental policies and laws aimed at protecting the Amazon forest and biome, as well as promoting sustainable development. We therefore present a summary of these standards aimed at environmental management in all countries of the greater Amazon region:

Brazil

- 1988 Brazilian Federal Constitution: Article 225 of the 1988 Brazilian Federal Constitution establishes that everyone has the right to an ecologically balanced environment, which is a common good for the people and essential for the quality of life. The article assigns to the Government and the community the duty to defend and preserve the environment for present and future generations. Article 225 includes points such as:

• Promoting environmental education at all levels of education and raising public awareness for environmental preservation;

• The unavailability of vacant lands or lands collected by States, due to discriminatory actions, necessary to protect natural ecosystems;

• The obligation of inspection and control, by the Public Authorities, of activities that are potential polluters, carried out by private individuals or by the State itself.

- National Environmental Policy (Law no. 6.938/1981): Established the National Environmental System (SISNAMA) and the National Environmental Council (CONAMA);

- National System of Conservation Units (SNUC) (Law nº 9.985/2000): Establishes the categories of conservation units and their rules of creation and management;

- Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm): Government program to reduce deforestation in the Legal Amazon.

- Forest Code (Law no. 12.651/2012): Regulates land use and establishes permanent preservation areas and legal reserves;

Bolivia

- Environmental Law (Law nº 1.333/1992): Establishes the basis for environmental protection, conservation of natural resources and pollution control;

- State Political Constitution (2009): Includes provisions on the protection of nature and the rights of Mother Earth;

- Mother Earth Rights Law (Law nº 71/2010): Recognizes nature as a subject of rights, establishing a framework for environmental protection based on the rights of Mother Earth;

- Landmark Law on Mother Earth and Integral Development for Good Living (Law No. 300/2012): Promotes a model of sustainable development, integrating environmental protection with social and economic well-being.

Peru

- General Environmental Law (Law no. 28611/2005): Establishes the legal framework for environmental protection and sustainable management of natural resources;

- Forestry and Wildlife Law (Law nº 29763/2011): Regulates the conservation and sustainable use of forests and wildlife, promoting participatory and inclusive management;

- Law of Protected Natural Areas (Law nº 26834/1997): Defines the creation, categorization, and management of protected natural areas;

- National Environmental Action Plan (PLANAA)8: Government strategy to address environmental challenges, including reducing deforestation and promoting sustainable development.

Colombia

- National Code of Renewable Natural Resources and Environmental Protection (Decree-Ley no. 2811/1974): Legal framework for the protection and sustainable use of natural resources;

- General Environmental Law (Law nº 99/1993): Creates the Ministry of the Environment and defines the National Environmental System (SINA);

- National Development Plan (PND)9: Includes goals for the conservation of biodiversity and the reduction of deforestation in the Colombian Amazon;

Ecuador

- Constitution of Ecuador (2008): Recognizes the rights of nature and establishes the responsibility of the state to protect the environment;

- Organic Environmental Code (COA) (2017)10: Consolidates and updates environmental legislation, promoting sustainable management of natural resources;

- The Equator Principles11: Guides actions for conservation and sustainable use of natural resources.

Guyana12

- Environmental Protection Act (1996): Establishes the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and regulates environmental management;

- Forest Conservation Law (1953): Regulates the management and conservation of forests.

French Guyana

- Déclaration Envisonnementale – PGRI de Guyane: Consists of plans and programs that bring together documents necessary for environmental assessment, in compliance with articles L122-4 to L122-17 of the Environmental Code (Code de l’environnement)13;

- Natura 2000 Network: Part of the European network of protected areas, French Guiana has several areas designated for the conservation of natural habitats and endangered species;

- Guiana Amazon Park: Created in 2007, it is one of the largest protected areas in France, with the aim of conserving biodiversity and promoting the sustainable development of local communities;

- Plan de Gestion Forestière14: Forest management program that regulates the sustainable exploitation of forests, ensuring the preservation of ecosystems;

Suriname

- National Action Adaptation Plan (NAP)15: Establishes strategies to increase the country’s resilience to climate change;

- National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Suriname (NBSAP Project)16: Aims at the conservation of biodiversity and the sustainable use of biological resources, promoting the integration of biodiversity policies into economic sectors;

Venezuela

- Organic Environmental Law (1976)17: Establishes the basis for environmental policy in Venezuela, promoting the conservation of natural resources and sustainable management of the environment;

- National Spatial Planning Plan18: Planning instrument that guides the sustainable use of the territory, including the management of natural resources and environmental protection;

In this transnational region, transformations and a new panorama are observed in the contemporary period. This is marked by the presence of multiple territorial divisions with delineations and usage restrictions aimed at conserving biodiversity and respecting the social and communal dynamics of Indigenous populations. Despite advances in conservation through these established territorial boundaries across the region, encompassing all countries that host parts of this biome, active pioneer fronts moving into the Amazon interior remain a persistent threat in the 21st century.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Pan-Amazon region presents contemporary challenges that require greater

care for nature and the social groups that live within it. It is necessary to develop

infrastructure, resources and actions aimed at reducing the various environmental

impacts, especially in cities, as well as fostering local economic activities to boost

the economy and generate income for society.

Moreover, this region exhibits internal dynamism and is intertwined with global

economic dynamics. As an integral part of a dynamic society, it reconfigures axes

and establishes new meanings and values within the region, altering patterns of

settlement and the flow of goods, people, and information. This triggers tensions

and socio-environmental conflicts, constituting one of the hallmarks, especially of

the Brazilian Amazon in the current period. Although it has protected territories,

the region is under pressure from nations and economic actors who see in this vast

geography the possibility of obtaining dominance, profit, and power.

Brazil, as an important geopolitical actor in South America, plays a key role in

several economic development, territorial and environmental integration agendas.

Like other countries, it faces the challenge of reconciling agendas and promoting

full living conditions for the society that lives in this region.

8 Available at: https://tinyurl.com/33dwrxc9. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

9 Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yckad6p8. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

10 Available at https://tinyurl.com/bdzmkhns. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

11 Available at: https://equator-principles.com/app/uploads/EP4_Spanish.pdf. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

12 Guyana’s set of environmental laws can be found at this link: https://tinyurl.com/5zea7ych. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

13 Available at https://tinyurl.com/3yaeefwp. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

14 Further information can be found at https://tinyurl.com/49fz8rwz. Accessed on July 25, 2024.

15 Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/NAP-Suriname-2020.pdf. Accessed on: 25 Jul 2024.

16 Available at: https://tinyurl.com/pmb9t8x7. Accessed on: 25 Jul 2024.

17 Available at: https://tinyurl.com/3f29tn8y. Accessed on: July 25, 2024.

18 Available at: http://sigta.minec.gob.ve/sigta/planes.php. Accessed on: July 25, 2024.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Pan-Amazon region presents contemporary challenges that require greater care for nature and the social groups that live within it. It is necessary to develop infrastructure, resources and actions aimed at reducing the various environmental impacts, especially in cities, as well as fostering local economic activities to boost the economy and generate income for society.

Moreover, this region exhibits internal dynamism and is intertwined with global economic dynamics. As an integral part of a dynamic society, it reconfigures axes and establishes new meanings and values within the region, altering patterns of settlement and the flow of goods, people, and information. This triggers tensions and socio-environmental conflicts, constituting one of the hallmarks, especially of the Brazilian Amazon in the current period. Although it has protected territories, the region is under pressure from nations and economic actors who see in this vast geography the possibility of obtaining dominance, profit, and power.

Brazil, as an important geopolitical actor in South America, plays a key role in several economic development, territorial and environmental integration agendas. Like other countries, it faces the challenge of reconciling agendas and promoting full living conditions for the society that lives in this region.

References

1. BRAZIL OF WATERS. Revealing the blue of green and yellow. Amazon Hydrographic Region. Available at: http://brasildasaguas.com.br/educacional/regioes-hidrograficas/regiao-hidrografica-do-amazonas/. Accessed on: 02 Jun. 2024.

2. BORGES, L. R. M. Territorial policies on the border: The Growth Acceleration Program and the transformations in Rondônia at the beginning of the century. XXI. São Paulo: Postgraduate Program in Human Geography – FFLCH/USP, 2012.

3. BORGES, L. R. M. Territorial policies and the electricity sector in Brazil: analysis of the effects of the construction of hydroelectric plants in the Amazon under the Growth Acceleration Program from 2007 to 2014. 2018. Doctoral Thesis (PhD in Human Geography) – Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018.

4. CAPOBIANCO, J. P R. Socio-environmental governance in the Brazilian Amazon in the 2000s. Doctoral Thesis. São Paulo: Postgraduate Program in Environmental Science, Institute of Energy and Environment of the University of São Paulo, 2017.

5. CASTRO, E. Territorial planning policies, deforestation, and border dynamics. New Naea Journals. V. 10, n. 2, p. 105-126, Dec. 2007. Available at http://goo.gl/QizefD. Accessed on: July 25, 2024.

6. CASTRO DE JESUS, A. B. The advancement of livestock farming in the municipality of Apuí/AM: brief geographical reflections on the pioneer dynamics of contemporary occupation. Transborder Geopolitical Magazine, [S.l.], v. 8, no. 2, p. 16-38, Mar. 2024.

7. CASTRO DE JESUS, A. B.; SILVA, F. B. A.; OLIVEIRA NETO, T. The Frontier Military Spatial Structure in the Brazilian Amazon. In: SENHORAS, E. M.; TEIXEIRA, V. M. (Org.). Geopolitics & International Relations: Empirical Agendas. 1ed.Boa Vista: Ioles, 2024, v. 1, p. 49-76.

8. CORRÊA, R. L. The periodization of the Amazon urban network. Brazilian Journal of Geography, v. 49, no. 3, p. 39-68, 1987.

9. CRAVEIRA, K. de O.; SILVA, F. B. A. da. AMACRO and pioneering fronts in the Amazon: deforestation, psychosphere and land issues. Transborder Geopolitical Magazine, [S.l.], v. 8, no. 2, p. 39-53, Mar. 2024.

10. CUISINIER-RAYNAL, A. La frontière au Pérou entre fronts et synapses. L’Espace Géographique, v. 3, 2001, pp. 213-230.

11. FONSECA, L. C. da.; TYBUSCH, J. S; BORBA, R. Law and sustainability I [Online electronic resource] organization CONPEDI/CESUPA, Florianópolis: CONPEDI, 2019.

12. HÉBETTE, J. Crossing the border: 30 years of studying the peasantry in the Amazon. Belém: EdUFPA, 2004.

13. IBGE. Amazon. Cities and states. Available at: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/am.html. Accessed on: 02 Jun. 2024.

14. LIMA, M. C. de. When tomorrow comes yesterday: the institutionalization of the metropolitan region of Manaus and the induction of the process of metropolization of space in the western Amazon. 2014.

15. MACHADO, L. O. Myths, and realities of the Brazilian Amazon in the international geopolitical context, 1540 – 1912. Doctoral Thesis, Universitad de Barcelona, 1989.

16. MELLO, N. A. de. Territorial policies in the Amazon. São Paulo: AnnaBlume, 2006.

17. NEPSTAD, D. C.; MOREIRA, A.; ALENCAR, A. A. The Burning Forest: Origins, Impacts and Prevention of Fire in the Amazon. Pilot Program for the Protection of Tropical Forests in Brazil, Brasília, Brazil, 1999.

18. NOGUEIRA, R. J. B.; OLIVEIRA NETO, T. Federalism, and environment in the Amazon: protected areas as a new political geography. L’Espace Politique. Revue en ligne de Géographie Politique et de Géopolitique, n. 31, 2017.

19. OLIVEIRA NETO, T. Road passenger transport in the Amazon. Doctoral Thesis in Human Geography, São Paulo: USP, 2024.

20. PORTO-GONÇALVES, C. W. Amazon: civilizational crossroads. Ongoing territorial tensions. 1 Ed. Rio de Janeiro: Consequência Editora, 2017.

21. RAZERA, A. Deforestation dynamics in a new frontier in southern Amazonas: an analysis of beef cattle farming in the municipality of Apuí. Manaus: INPA/UFAM, 2005.

22. REIS, R. G.; LEAL, M. L. M. Analysis of the relationship between hot spots and deforestation in the municipality of Lábrea, southern Amazonas. Brazilian Environmental Magazine, v. 8, no. 3, 2020.

23. SILVA, F. B. A. da; LIMA, M. C. de; YANO, Y. S. Territorial management in Amazonas: The state and centralities. Revista Tocantinense de Geografia, [S. l.], v. 12, no. 27, p. 73–91, 2023.

24. SILVA, G. S. C; ATTANASIO JUNIOR, M. R. Brazil in front of the Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm). Diadema, 2023. 13 f.

25. SILVA, R. G. da C.; SILVA, V. V. da; MELLO-THÉRY, N. A. de; LIMA, L. A. P. New frontier of expansion and protected areas in the state of Amazonas. Mercator, v 20, pp. 1-13, 2021.

26. TAVARES, M. G. da C. The Brazilian Amazon: historical-territorial formation and perspectives for the 21st century. GEOUSP Space and Time (Online), São Paulo, Brazil, v. 15, no. 2, p. 107–121, 2011.

27. WANDERLEY, L. J. Gold rush, mining, and mineral frontier in the Amazon. Sapiência Magazine: Society, Knowledge, and Educational Practices. Dossier: Mineral extraction, conflicts, and resistance in the Global South. V.8, N.2, p.113-137, 2019.

2. BORGES, L. R. M. Territorial policies on the border: The Growth Acceleration Program and the transformations in Rondônia at the beginning of the century. XXI. São Paulo: Postgraduate Program in Human Geography – FFLCH/USP, 2012.

3. BORGES, L. R. M. Territorial policies and the electricity sector in Brazil: analysis of the effects of the construction of hydroelectric plants in the Amazon under the Growth Acceleration Program from 2007 to 2014. 2018. Doctoral Thesis (PhD in Human Geography) – Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018.

4. CAPOBIANCO, J. P R. Socio-environmental governance in the Brazilian Amazon in the 2000s. Doctoral Thesis. São Paulo: Postgraduate Program in Environmental Science, Institute of Energy and Environment of the University of São Paulo, 2017.

5. CASTRO, E. Territorial planning policies, deforestation, and border dynamics. New Naea Journals. V. 10, n. 2, p. 105-126, Dec. 2007. Available at http://goo.gl/QizefD. Accessed on: July 25, 2024.

6. CASTRO DE JESUS, A. B. The advancement of livestock farming in the municipality of Apuí/AM: brief geographical reflections on the pioneer dynamics of contemporary occupation. Transborder Geopolitical Magazine, [S.l.], v. 8, no. 2, p. 16-38, Mar. 2024.

7. CASTRO DE JESUS, A. B.; SILVA, F. B. A.; OLIVEIRA NETO, T. The Frontier Military Spatial Structure in the Brazilian Amazon. In: SENHORAS, E. M.; TEIXEIRA, V. M. (Org.). Geopolitics & International Relations: Empirical Agendas. 1ed.Boa Vista: Ioles, 2024, v. 1, p. 49-76.

8. CORRÊA, R. L. The periodization of the Amazon urban network. Brazilian Journal of Geography, v. 49, no. 3, p. 39-68, 1987.

9. CRAVEIRA, K. de O.; SILVA, F. B. A. da. AMACRO and pioneering fronts in the Amazon: deforestation, psychosphere and land issues. Transborder Geopolitical Magazine, [S.l.], v. 8, no. 2, p. 39-53, Mar. 2024.

10. CUISINIER-RAYNAL, A. La frontière au Pérou entre fronts et synapses. L’Espace Géographique, v. 3, 2001, pp. 213-230.

11. FONSECA, L. C. da.; TYBUSCH, J. S; BORBA, R. Law and sustainability I [Online electronic resource] organization CONPEDI/CESUPA, Florianópolis: CONPEDI, 2019.

12. HÉBETTE, J. Crossing the border: 30 years of studying the peasantry in the Amazon. Belém: EdUFPA, 2004.

13. IBGE. Amazon. Cities and states. Available at: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/am.html. Accessed on: 02 Jun. 2024.

14. LIMA, M. C. de. When tomorrow comes yesterday: the institutionalization of the metropolitan region of Manaus and the induction of the process of metropolization of space in the western Amazon. 2014.

15. MACHADO, L. O. Myths, and realities of the Brazilian Amazon in the international geopolitical context, 1540 – 1912. Doctoral Thesis, Universitad de Barcelona, 1989.

16. MELLO, N. A. de. Territorial policies in the Amazon. São Paulo: AnnaBlume, 2006.

17. NEPSTAD, D. C.; MOREIRA, A.; ALENCAR, A. A. The Burning Forest: Origins, Impacts and Prevention of Fire in the Amazon. Pilot Program for the Protection of Tropical Forests in Brazil, Brasília, Brazil, 1999.

18. NOGUEIRA, R. J. B.; OLIVEIRA NETO, T. Federalism, and environment in the Amazon: protected areas as a new political geography. L’Espace Politique. Revue en ligne de Géographie Politique et de Géopolitique, n. 31, 2017.

19. OLIVEIRA NETO, T. Road passenger transport in the Amazon. Doctoral Thesis in Human Geography, São Paulo: USP, 2024.

20. PORTO-GONÇALVES, C. W. Amazon: civilizational crossroads. Ongoing territorial tensions. 1 Ed. Rio de Janeiro: Consequência Editora, 2017.

21. RAZERA, A. Deforestation dynamics in a new frontier in southern Amazonas: an analysis of beef cattle farming in the municipality of Apuí. Manaus: INPA/UFAM, 2005.

22. REIS, R. G.; LEAL, M. L. M. Analysis of the relationship between hot spots and deforestation in the municipality of Lábrea, southern Amazonas. Brazilian Environmental Magazine, v. 8, no. 3, 2020.

23. SILVA, F. B. A. da; LIMA, M. C. de; YANO, Y. S. Territorial management in Amazonas: The state and centralities. Revista Tocantinense de Geografia, [S. l.], v. 12, no. 27, p. 73–91, 2023.

24. SILVA, G. S. C; ATTANASIO JUNIOR, M. R. Brazil in front of the Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm). Diadema, 2023. 13 f.

25. SILVA, R. G. da C.; SILVA, V. V. da; MELLO-THÉRY, N. A. de; LIMA, L. A. P. New frontier of expansion and protected areas in the state of Amazonas. Mercator, v 20, pp. 1-13, 2021.

26. TAVARES, M. G. da C. The Brazilian Amazon: historical-territorial formation and perspectives for the 21st century. GEOUSP Space and Time (Online), São Paulo, Brazil, v. 15, no. 2, p. 107–121, 2011.

27. WANDERLEY, L. J. Gold rush, mining, and mineral frontier in the Amazon. Sapiência Magazine: Society, Knowledge, and Educational Practices. Dossier: Mineral extraction, conflicts, and resistance in the Global South. V.8, N.2, p.113-137, 2019.

Published in

Volume 4, Issue 8, 2024

Keywords

BORDER

URBAN NETWORK

ENVIROMENTAL CONSERVATION

AMAZON

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals