Circular Economy Disclosure in European Banks: A Substantive Commitment or Symbolic Compliance?

Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between Circular Economy Disclosure (CED) and environmental performance in European banks by analysing the information published on their official websites. Grounded in legitimacy theory, it examines whether higher environmental performance corresponds to more extensive CED, distinguishing between substantive and symbolic approaches. The findings, based on a sample of 107 listed European banks, reveal a positive association between environmental performance and CED. This supports the substantive legitimacy perspective, indicating that CED practices tend to align with actual sustainability engagement rather than serving as mere symbolic commitment.

Article

INTRODUCTION

Sustainability has become a global priority for organizations, driven by regulatory pressures, stakeholder expectations, and pressing environmental challenges such as climate change and resource depletion (Meza-Ruiz et al., 2017). Linear production models – based on extraction, production, and disposal – pose significant threats to ecosystems and human well-being (Lüdeke-Freund et al., 2019). In response, many organizations are incorporating sustainability into their business strategies, recognizing its benefits for both society and the environment (Sardana et al.,2020). Within this context, the Circular Economy (CE) is increasingly recognised as a crucial strategy for promoting sustainability, as it aims to minimise environmental impacts and support long-term sustainable development (Tukker, 2015). By extending the lifecycle of resources, the CE promotes waste reduction and enhances over all resource efficiency.

Though commonly associated with manufacturing, CE practices are also relevant for the banking sector (Zahid et al., 2024). Indeed, banks can support the CE transition externally – by offering tailored financial products, networks, and strategic support – and internally – by adopting sustainable operations such as energy efficiency, waste recycling, and new technologies (Fraccalvieri et al., 2025).

Given their influential role, banks are expected to disclose CE practices transparently, ensuring stakeholders understand both external initiatives and internal sustainability efforts, including adherence to the 3R principles: reduce, reuse, recycle (Fraccalvieri et al., 2025).

Despite its growing importance, CE Disclosure (CED) in banking remains still underexplored. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap by examining whether banks’ environmental performance aligns with their CED, investigating the presence of greenwashing using the substantive and symbolic legitimacy framework. Specifically, this study focuses on banks’ official websites as primary communication channels for sustainability (Schröder, 2021), specifically within the European banking context, characterised by distinct structures and strong stakeholder pressure (Lazarides & Drimpetas, 2016).

The remainder of this work is organised as follows: Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature on the topic; Section 3 presents the theoretical framework and the hypothesis development; Section 4 describes the research methodology; Section 5 presents the empirical results along with their discussion; Section 6 pro vides the conclusions

LITERATURE REVIEW

The critical relevance of banks in advancing the transition to a CE has attracted the attention of academics who have started to investigate this topic. A first strand of research has explored the role of banks in supporting the CE. Goovaerts & Verbeek (2018) identified two key contributions: enabling the CE transition through financial, legal, and advisory services, and adapting internal models to address linear and circular risks. Yet, as Zhelyazkova (2020) noted, the lack of harmonised regulations – especially in developed countries – limits banks’ proactive involvement, unlike in countries such as China, Brazil, and Peru, where CE lending is incentivised. To address this gap, Ozili & Opene (2021) proposed a structured CE approach, including shared definitions, standardized finance guidelines, green banks, dedicated credit lines, staff training, and stronger governance. Rataj et al. (2025) further observed that while sustainability goals dominate early CE initiatives, financial returns become central over time, with frontline staff playing a key role in promoting CE values and fostering stakeholder knowledge exchange.

A second research strand has focused on the benefits of CE adoption in banking. Ozili (2021) highlighted advantages such as loan diversification, enhanced reputation, and profitability in circular sectors. Broader financial system benefits include CE-linked insurance innovations, better sustainability-adjusted returns, and expanded microfinance and collaborative funding for circular ventures. A third strand has examined CED in the banking sector. Zahid et al. (2024) showed that both Islamic and conventional banks in Pakistan disclose CE practices aligned with the SDGs. Keskin & Esen (2025) identified key CE themes – waste, renewables, emissions, and sustainable investing – but noted poor readability of reports. Fraccalvieri et al. (2025) uniquely investigated CED determinants, finding that size, online visibility, and international presence foster disclosure.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development In line with prior research on disclosure practices in banking (e.g., Branco & Rodrigues, 2006; Fraccalvieri et al., 2025), this study considers legitimacy theory to analyse the determinants of CED. Legitimacy theory posits that organisations rely on societal approval to operate, which they gain by aligning with the norms and expectations embedded in an implicit social contract (Suchman, 1995; Deegan, 2002).

To achieve, maintain, and repair legitimacy, disclosure represents a crucial link between organisations and society. Indeed, disclosure serves as a tool to communicate conformity with stakeholder expectations (Farneti et al., 2019). However, the process of legitimation is not uniform and can be examined through two main behavioural perspectives: substantive and symbolic approaches (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990). According to the substantive approach, meeting societal expectations requires realistic and material modifications to organisational strategies and operations (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990; Lodhia et al., 2023). Therefore, sustainability disclosure serves as a tool for stakeholders to evaluate whether strategic adjustments have been effectively translated into concrete actions (Nicolò et al., 2023). In line with this perspective, banks with stronger environmental performance are expected to disclose more CE information.

Conversely, the symbolic approach is primarily concerned with impression management and greenwashing, wherein organisations focus more on shaping stakeholder perceptions rather than implementing substantive changes to their operations (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990; Lodhia et al., 2023). In this perspective, a gap exists between disclosure practices and effective organisational performance and activities (Ashforth & Gibbs,1990). Hence, banks with weaker environmental performance may use CED to create the appearance of sustainability, aiming to protect their image without making substantive changes.

Given their high public visibility, banks face intense legitimacy pressures (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Hossain & Reaz, 2007), with growing expectations for transparency and environmental accountability (Zahid et al., 2024). Hence, voluntary disclosure becomes a strategic tool to build trust and signal environmental commitment (Mobus, 2005; Fraccalvieri et al., 2025). In light of this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: There is a relationship between environmental performance and the level of CED provided by European banks.

METHODOLOGY

This study analyzes 107 publicly listed European banks from 26 countries. In the first phase, 330 banks were identified from the Refinitiv Eikon database as of 2023. However, after accounting for missing values, 223 institutions were removed. The CED Score (CEDS) is the dependent variable of this study, which captures the extent to which banks disclose CE information through their official websites. To measure this variable, a content analysis on banks’ official websites was conducted.

This study employs the coding framework originally developed by Fraccalvieri et al. (2025). It provides a comprehensive assessment of banks’ engagement with CE principles, and it is structured into two primary areas: (A) supporting the circular transition of firms and (B) internal implementation of CE practices. These two categories provide a holistic evaluation of both external and internal commitments to CE principles.

For this study, an unweighted dichotomous scoring approach was applied (Vitolla et al., 2022). Therefore, each item in the index was assigned a score of 1 if relevant information was found on the bank’s website and 0 if it was absent. Consequently, the dependent variable ranges from 0 to 50, reflecting the comprehensiveness of a bank’s CED.

The independent variable of this study is represented by ENV_PILLAR. It indicates a bank’s environmental impact by evaluating different ecological factors – air quality, land use, water resources, and broader ecosystem considerations. It serves as an indicator of a bank’s effectiveness in managing environmental risks. It is used as a measure of environmental performance (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2021) and can assume values ranging from 0 to 100, expressed as a percentage. The control variables included in the model are Profitability, Size, Age, Liquidity, Internet_Visibility, Social_Media. Profitability is proxied by the ratio of net income to total assets (Kiliç & Kuzey, 2019). Size is expressed as the natural logarithm of the number of bank branches (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006). Age is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of years elapsed since the bank was established (Talavera et al., 2018). Liquidity is proxied by the loans-to-deposits ratio, which measures the extent to which a bank’s lending activity is covered by its deposit base (Tamunosiki et al., 2017). Internet_Visibility is obtained by taking the natural logarithm of the number of search results on “Google.com” that included the bank’s name in the year 2023 (Fraccalvieri et al., 2025). Social_Media indicates the presence of banks on the main social media. It can take values from 0 to 9, relating to the presence of the bank on the following social media platforms: LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube, TikTok, Bluesky, Threads, and WeChat (L’Abate et al., 2023). To test the hypothesis made explicit in the previous Section, an OLS regression was employed. Specifically, the formal equation is as follows:

CEDSi = 𝛽0 +𝛽1 ENV_PILLARi +𝛽2 Profitabilityi +𝛽3 Sizei+

+𝛽4 Agei +𝛽5 Liquidityi +𝛽6 Internet_Visibilityi +𝛽6 Social_Mediai + ԑi

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

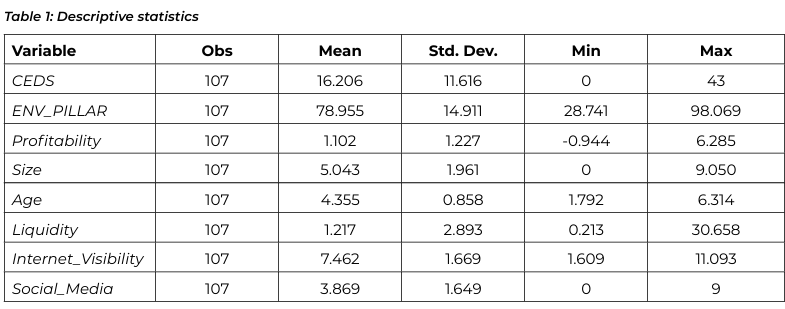

Table 1 illustrates the descriptive statistics, while Table 2 shows the correlation matrix and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis.The descriptive statistics indicate a low average value of the dependent variable CEDS. Indeed, it is equal to 16.21, thus showing that, on average, banks disclose little CE information through their official websites. Additionally, the highest value for this variable is 43, demonstrating that no sample bank provides information on all 50 items considered in the disclosure index. As regards the independent variable of this study, ENV_PILLAR shows an average value of about 79%, thereby indicating that the European banks, on average, demonstrate a strong commitment to environmental performance

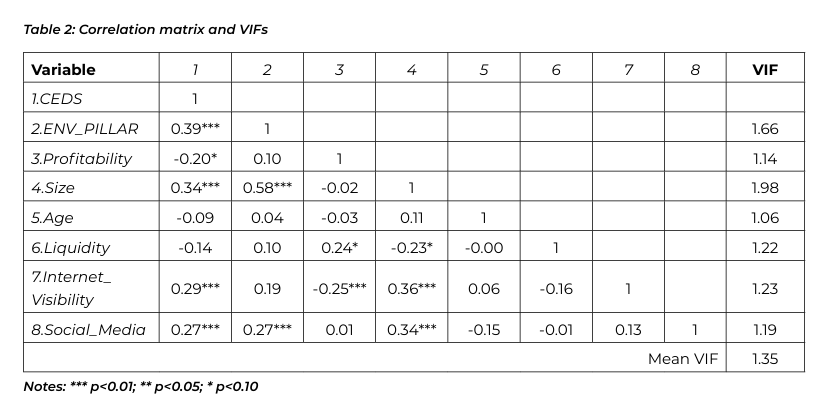

Regarding the correlation analysis, the highest coefficient equals 0.58, between ENV_PILLAR and Size. Since it does not exceed the critical thresholds commonly accepted in literature, it can be concluded that multicollinearity is not a concern in this analysis. The absence of multicollinearity issues is further reinforced by the VIF analysis.

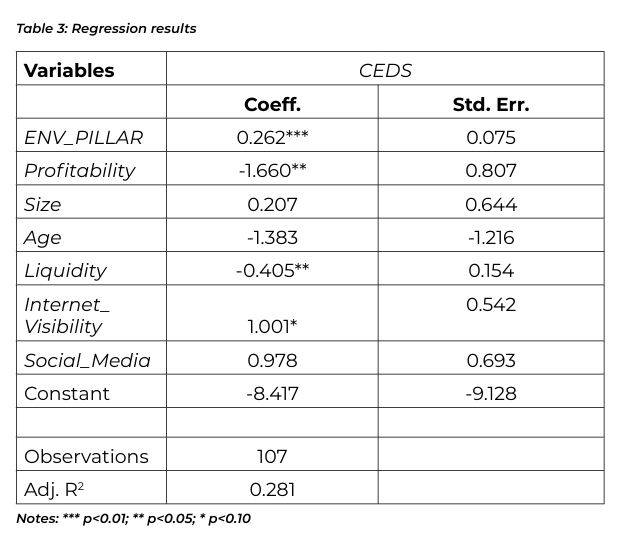

Table 3 shows the empirical results of the analysis. In particular, the findings show a positive (𝛽=0.262) and highly significant (p<0.01) relationship between ENV_PILLAR and CEDS, thus supporting the research hypothesis of this study (H1). This indicates that European banks with higher environmental performance tend to disclose more information related to CE practices on their official websites. The alignment between actual performance and disclosure supports the substantive view of legitimacy theory, which holds that organisations gain legitimacy by transparently communicating genuine achievements (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990; Mobus, 2005).

This positive association reflects banks’ response to increasing transparency demands in the context of the CE transition. By engaging in environmental initiatives and communicating results effectively, banks reinforce their credibility and long-term legitimacy, helping to mitigate stakeholder scepticism. Moreover, using official websites as a disclosure channel allows banks to reach a wide audience quickly and dynamically. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Fraccalvieri et al., 2025), websites serve as strategic tools for delivering sustainability-related information.

CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between environmental performance and CED provided by banks through their official websites. More specifically, the objective of this work was to determine whether the environmental practices adopted by banks were substantive or symbolic in relation to the CE information disclosed. The results revealed a positive association between environmental performance and the level of CE information disseminated by European banks through their official websites. Therefore, a substantive commitment related to CE actions and practices is observed within the European banking context . This study contributes to the literature by examining how banks disclose their environmental performance through CED, addressing a gap in research that has

largely overlooked the banking sector. It highlights the growing use of corporate websites for sustainability communication – offering real-time, accessible information – yet still underexplored in banking. It also analyzes the link between environmental performance and CED, adding to the debate on whether disclosures reflect real actions or are symbolic.Practically, banks are encouraged to use websites transparently to build trust and legitimacy. Standard setters should create clear guidelines for CED, while policymakers could introduce incentives to promote transparent and genuine disclosure.

Limitations of this study include the sample size and the use of environmental performance as a proxy for CE commitment. Future research should broaden the sample and develop more specific CE performance measures.

References

2. Castelo Branco, M., & Lima Rodrigues, L. (2006). Communication of corporate social responsibility by Portuguese banks: A legitimacy theory perspective. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 11(3), 232-248.

3. Deegan, C. (2002). Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures–a theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282-311.

4. Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122-136.

5. Duque-Grisales, E., & Aguilera-Caracuel, J. (2021). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. Journal of Business Ethics, 168(2), 315-334.

6. Farneti, F., Casonato, F., Montecalvo, M., & de Villiers, C. (2019). The influence of integrated reporting and stakeholder information needs on the disclosure of social information in a state-owned enterprise. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(4), 556-579.

7. Fraccalvieri, I., L’Abate, V., Raimo, N., Vitolla, F., & Bussoli, C. (2025). Transparent Banking: Unveiling the Drivers of Online Circular Economy Disclosure in European Banks. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32(3), 3342-3354.

8. Goovaerts, L., & Verbeek, A. (2018). Sustainable banking: finance in the circular economy. Investing in Resource Efficiency: The Economics and Politics of Financing the Resource Transition, 191-209.

9. Hasan, R. & Wang, W. (2021), “Social media visibility, investor diversity and trading consensus”, International Journal of Managerial Finance, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 25-48.

10. Hossain, M., & Reaz, M. (2007). The determinants and characteristics of voluntary disclosure by Indian banking companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 14(5), 274-288.

11. Keski ̇n, H., & Esen, E. (2025). Themes and readability of integrated reports of banks from a circular economy perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(2), 321-340

12. Kiliç, M., & Kuzey, C. (2019). Determinants of climate change disclosures in the Turkish banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(3), 901926.

13. L’Abate, V., Raimo, N., Rubino, M., & Vitolla, F. (2023). Social media visibility and intellectual capital disclosure. An empirical analysis in the basketball clubs. Measuring Business Excellence, 28(1), 52-68.

14. L’Abate, V., Esposito, B., Raimo, N., Sica, D., & Vitolla, F. (2024a). Flying toward transparency: revealing circular economy disclosure drivers in the airline industry. The TQM Journal.

15. L’Abate, V., Raimo, N., Albergo, F., & Vitolla, F. (2024b). Social media to disseminate circular economy information. An empirical analysis on Twitter. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(1), 528 539.

16. Lazarides, T., & Drimpetas, E. (2016). Defining the factors of Fitch rankings in the European banking sector. Eurasian Economic Review, 6(2), 315-339.

17. Lodhia, S., Kaur, A., & Kuruppu, S. C. (2023). The disclosure of sustainable development goals (SDGs) by the top 50 Australian companies: substantive or symbolic legitimation?. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(6), 1578-1605.

18. Lüdeke‐Freund, F., Gold, S., & Bocken, N. M. (2019). A review and typology of circular economy business model patterns. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 23(1), 36-61.

19. Luft Mobus, J. (2005). Mandatory environmental disclosures in a legitimacy theory context. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18(4), 492-517.

20. Meza-Ruiz, I. D., Rocha-Lona, L., del Rocío Soto-Flores, M., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Kumar, V., & Lopez-Torres, G. C. (2017). Measuring business sustainability maturity-levels and best practices. Procedia Manufacturing, 11, 751-759.

21. Nicolò, G., Andrades‐Peña, F. J., Ferullo, D., & Martinez‐Martinez, D. (2023). Online sustainable development goals disclosure: A comparative study in Italian and Spanish local governments. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(4), 1490-1505.

22. Ozili, P. K. (2021). Circular economy, banks, and other financial institutions: what’s in it for them?. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 1(3), 787-798.

23. Ozili, P. K., & Opene, F. (2021). The role of banks in the circular economy. Available at SSRN 3778196.

24. Rataj, O., Alcorta, L., Raes, J., Yilmaz, E., Riccardo, L. E., & Sansini, F. (2025). Sustainability vs profitability: Innovating in circular economy financing practices by European banks. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 53, 1-16.

25. Salesa, A., León, R., & Moneva, J. M. (2023). Airlines practices to incorporate circular economy principles into the waste management system. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(1), 443-458.

26. Sardana, D., Gupta, N., Kumar, V., & Terziovski, M. (2020). CSR ‘sustainability’practices and firm performance in an emerging economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120766.

27. Schröder, P. (2021). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) website disclosures: empirical evidence from the German banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(5), 768-788.

28. Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of management review, 20(3), 571-610.

29. Talavera, O., Yin, S., & Zhang, M. (2018). Age diversity, directors’ personal values, and bank performance. International Review of Financial Analysis, 55, 60-79.

30. Tamunosiki, K., Giami, I. B., & Obari, O. B. (2017). Liquidity and performance of Nigerian banks. Journal of Accounting and Financial Management, 3(1), 34-46.

31. Tukker, A. (2015). Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy–a review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 97, 76-91.

32. Vitolla, F., Raimo, N., Rubino, M., & Garzoni, A. (2022). Broadening the horizons of intellectual capital disclosure to the sports industry: evidence from top UEFA clubs. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(1), 142-162.

33. Yongvanich, K., & Guthrie, J. (2007). Legitimation strategies in Australian mining extended performance reporting. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 11(3), 156-177.

34. Zahid, M., Hayat, M., Rahman, H. U., & Ali, W. (2024). Is the financial industry ready for circular economy and sustainable development goals? A case of a developing country. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 16(5), 962-992.

35. Zhelyazkova, V. (2020). The Role of Banks for the Transition to Circular Economy. In Circular Economy-Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Applications. IntechOpen

Published in

Volume 5, Issue 9 2025

Keywords

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals