Evolution of Cross-Border Cooperation in the European Union – Challenges and Opportunities1

Abstract

The importance of cross-border cooperation systems along the external and internal borderlines of the European Union has been increasing since the last enlargements (in 2004 and 2007, 2013). Cross-border cooperation forms gained greater importance in the Hungarian national policy, in the cohesion policy of the European Union as well as in the formation of neighbourhood policy. In the last few years, however, the three most recent crises of the European Union – the 2015 migration crisis, the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war – and the socioeconomic impacts of all these crises have resulted in the re-discovery of borders. The European discourse changed fundamentally: instead of the elimination of borders and border obstacles, the issue of security has come to the fore, resulting in reclosing of borders, construction of new borders and application of more stringent border control. The aim of the study is to examine the institution-building process of cross-border territorial cooperation processes in the European Union. Analysing the legal framework for cross-border cooperation established by the Council of Europe and European Union can be recognised as a response to the lack of legal and institutional instruments of cross-border cooperation.

1 The manuscript was finalized on 30 March 2023.

Article

INTRODUCTION

In the second half of the 20th century, the countries and leading politicians of Western Europe recognised the importance of cooperation in maintaining their economic and political competitiveness. Establishing the sui generis legal and institutional system of European integration, based on the four freedoms, had a considerable impact on the position and role of member states’ borders. The European integration process contributed to the gradual breaking down of internal borders and the creation of the Schengen border system. This process gradually replaced the earlier divisive nature of borders by an increasingly unifying role. This led to two new challenges: supranational integration and cross-border regionalism.

However, implementing the concept of “Europe without borders” was not only a main objective within the founding Member States of the European integration and at the central administrative level of the participating Member States, but also at the subnational (local and regional) level. Such cooperation opportunities became increasingly widespread, thus strengthening the economic and social cohesion of Europe and the process of democratisation.

The Council of Europe (hereinafter: CoE) initially played a crucial role in strengthening the competences of subnational levels and in creating the legal and institutional conditions for local and regional democracy and the values of self-governance. Later, the increased role of subnational levels became a European integration concept and a part of the regional policy of the European Union, its framework being laid down in the Single European Act. However, for a long time, the issue of cross-border cooperation was mainly considered by the European Union in the context of structural funds implementation. In the meantime, a “bottom-up” process emerged and gave rise to subnational euroregional movements with a political agenda supported by bottom-up political, economic, ethnic, and cultural elements. According to the Charter for Border and Cross-border Regions,

Cross-border cooperation helps to mitigate the disadvantages of borders, overcome the peripheral status of the border regions in their country, and improve the living conditions of the population in border regions. It encompasses all cultural, social, economic, and infrastructural spheres of life. (AEBR, 2015: 3)

The new cross-border political concept of these pursuits lived on under the name of “new regionalism” in the late 1980s, gaining dominance not only in EU member states, but also in Central and Eastern European countries to become a means of preparation for EU accession. (Keating, 1998) Cross-border cooperation does not come from the European Union itself, it is a bottom-up process, originating from local initiatives. As a result, the European Union gradually and systematically incorporated the area of cross-border cooperation into its repertoire of integration policies. (Scott, 2019: 45–68).

It became evident that European, national, regional, and local decision makers were required to follow a more intensive cooperation policy and offer stronger mutual support to solve the problems that border and cross-border regions were facing. According to the famous two models of multi-level governance introduced by Hooghe and Marks, the first model can be considered federalist, as it is defined by the share of competencies between territorial entities existing beside each other. The second is a rather networked-based solution where jurisdictions can be overlapped. (Hooghe and Marks, 2001: 4–29) In its White Paper, the European Commission published the concept of new European governance (COM (2001) 428

final), based on the principles of openness, participation, effectiveness, accountability, and coherence, met the requirements of an enlarged EU. The document can be classified under the first model described by Hooghe and Marks, while the White Paper on Multi-level Governance released by the Committee of the Regions in 2009 followed the second model, including the presentation of macro-regional strategies and cross-border cooperation structures. (CdR 89/2009 final).

Because of the permeability of the Union’s internal borders, they also create new spatial structures and new forms of governance across the existing administrative borders in accordance with subsidiarity and multi-level governance policies. (Kaiser, 2014: 53–60). These changes suggest alterations within the ideas of regions and territories, borders, identities, and relevant forms of governance, as well as concrete practices of cross-border planning. This challenge is apparent at various spatial scales, from local to regional and from national to supra-national. (Paasi, 2019: 6990) However, cross-border cooperation – local, regional and international – can only fulfil its real role if there is a constitutional and administrative environment capable of harmonizing the different legal structures and competencies and also if:

• the legal/administrative set-up of the member states significantly differs from each other;

• the decision competences, resources and powers of the co-operating administrative units differ in several respects;

• institutional diversity has led to diff iculties resulting in many different forms of cross-border cooperation, where there is no commonly accepted organisational system. (Peyrony, 2020: 219–240)

The new kind of cross-border relations in the Central and Eastern European countries were subject to various influences due to their specific features. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the launch of the democratisation process in the former communist bloc at the time of the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty, the concepts of “Borderless Europe” and an “ever closer Union” seemed feasible in the near future. Following the regime change, several initiatives were born in the border areas of the Central and Eastern European region with the aim of creating subnational level crossborder relations, however, these initiatives were hindered by politics, the inexperience of the players, and an immature legal and administrative environment.

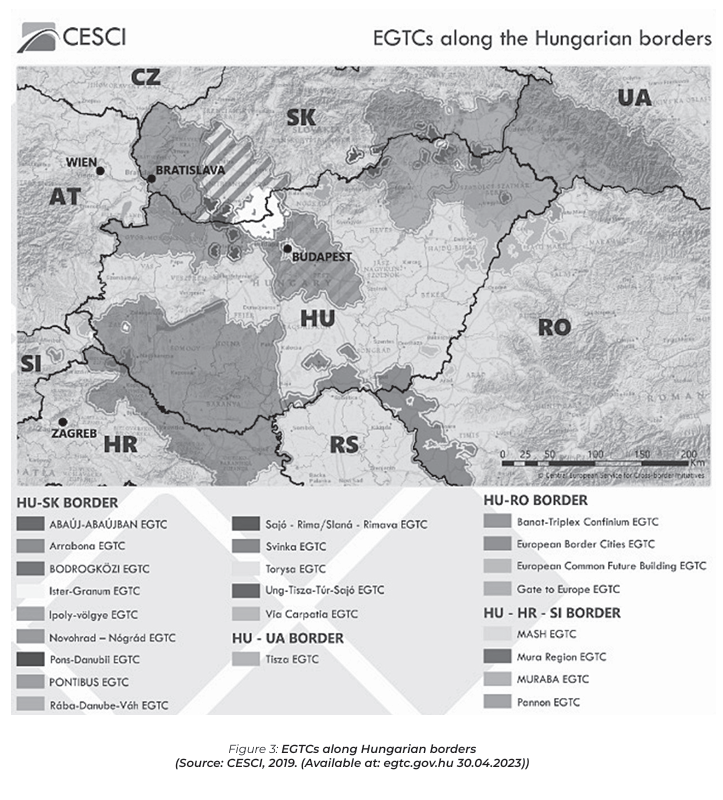

By now the borders and border areas of Hungary enjoy a nearly full coverage of cooperation, the most common ones being Euroregions, since the late 1990s, and the European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (hereinafter referred to as EGTC) from 2007 on. In the process of subnational level integration, cross-border cooperation forms gained greater importance in the Hungarian national policy, in the cohesion policy of the European Union as well as in the formation of neighbourhood policy. Hungary’s borders represent all border types of the European Union, since it has seven borders of six different statuses, where cooperation can be created under different legal and governance conditions.

Hungary borders on

• an “old” member state (Austria);

• member states that joined the EU at the same time as Hungary (Slovakia and Slovenia);

• a member state that joined the EU in 2007 (Romania);

• a member state that joined in the European Union on 1st July 2013 (Croatia);

and

• states aspiring to join the EU but facing numerous legal and political challenges (Serbia and war-torn Ukraine).

The three most recent crises of the European Union – the 2015 migration crisis, the COVID pandemic in 2020–2021, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 – have fundamentally shaken and challenged the project of borderless Europe. Each crisis has impacted the system of European border regimes and the freedom of movement: several EU member states closed their borders to migrants. Moreover, the Russian aggression against Ukraine has returned territorial sovereignty to the centre of the European discourse, as the most salient symbol of territorial sovereignty is the state border.

The topic has relevance at both the international and European levels, as the problem of border regions has gained even more importance in recent years in both EU policies and regional research. For those involved in cross-border cooperation, it has always been clear that cooperation was always a key aspect (rather than a marginal one), of the European project. Therefore, with a view to managing the impacts of crises, cross-border cooperation should be restored to its place at the heart of EU policies and public opinion.

THE EVOLUTION OF INSTITUTIONALISED CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION

For a long time, there were no uniform regulations on the institutional forms of cross-border cooperation. Cooperation initially appeared in various organizational formats, therefore a wide range of grouping methods were developed both in practice and in the literature. In the field of institutionalization, the most used and the widest grouping aspect to classify cooperation in organized forms, in which Perkmann’s concept (Perkmann, 2002) from international literature serves as a starting point. Perkmann distinguishes between cooperation by geographic

extension and whether there is regional contact between them. This grouping method is also used in Hungarian literature (Baranyi, 2007; Hardi, 2004; NáraiRechnitzer, 1999), and gives a good overview for the analysis of the cooperation in the Carpathian Basin.

In addition to literature criteria, the grouping methods of practical guidelines of the European institutions are representative for the definition of organised forms of cross-border cooperation (MOT, 2008; INTERACT, 2008; CoR, 2009; Zillmer, 2018). The practical guidelines compiled in 2000 in the framework of the AEBR project called Linkage, Assistance and Cooperation for the European Border Regions (LACE) clearly distinguishes between three main types of cross-border cooperation, considering the level of cooperating partners and the territorial connection (AEBREC, 2000). It differentiates between local, regional, and national participants in the vertical system of multi-level governance, and in this respect, it represents their network horizontally, depending on whether immediately adjacent territories are interconnected or whether the common interests of the regional aspect arising

at regional level are brought together in a broader geographical area. Based on institution building, we can distinguish between the following types of cooperation:

1. Transnational cooperation. Cooperation with the neighbouring territories can be established between states or larger territorial units with a common border, though this form of cross-border cooperation is the least widespread and – given its size and complexity – is also the most difficult to institutionalize. Such cooperations are mainly motivated by the common treatment and development of a territory fragmented by borders; it is determined by a large-scale geographic spatial structure, the objective of which is to create the cohesive, natural relations of a natural, historical, or cultural macro region. In this context, borders only indirectly motivate cooperation; however, there is a strong state involvement in their work.

(AEBR-EC, 2000: 85–86; Baranyi, 2007: 245) That cooperation, consisting of several countries of Europe, functions as working communities. Examples include the Pyrenean Working Community, the Western Alps Working Community, the Jura Working Community, the Galicia – Northern-Portugal Working Community, Working Community of the Danube Regions, the Alps – Adriatic Alliance.

2. Cross-border cooperation. Another form of cooperation between neighbouring regions has developed from the cooperation between sub-national actors (local or regional authorities, as well as other economic and social partners). Their geographic scope is relatively small, they usually do not go beyond the territorial/ regional frameworks (Baranyi, 2007: 238–240; Perkmann, 2002:7). That is, the main participants and organizers of the cooperation are in all cases grassroots, sub-state entities whose operation – due to the specific features of different legal systems – can often be influenced/limited by the member states’ regulatory frameworks. Cross-border cooperation of this type forms gradually deepening, integrated

organizations and there is an increasing need for a permanent and compulsorily established cross-border joint institutional system. (AEBR-EC, 2000: 12–13; 84–98) The forms of cooperation developed in this way generally meet the criteria of the Euroregion; in addition, they can establish everyday contact and the chance for long-term survival and cooperation. (Telle, 2017: 93–110).

Examples of larger cooperation include, but are not limited to, the EUROREGIO (D/NL) established on the borders of Germany and the Netherlands, having existed since 1958; the Rhine – Waal Euroregion (D/NL) working at the same place; the PAMINA (Palatinate–Middle Upper Rhine–Northern Alsace D/F) and the Elbe–Labe Euroregion (D/CZ). By the 2000s nearly 200 similar structures were created.

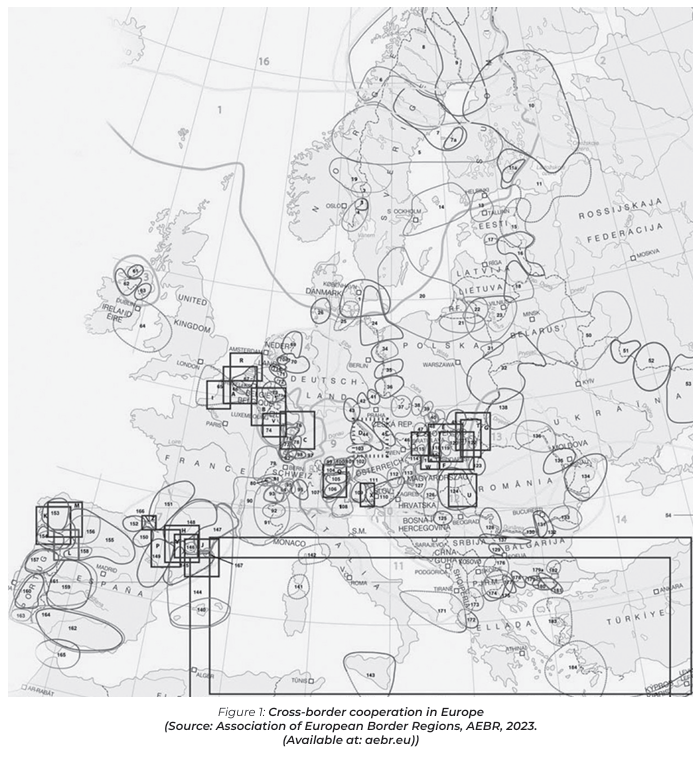

3. Interregional cooperation. Interregional cooperations includes those established between non-neighbouring regions as multilateral relations. They can be small-scale – such as twinned towns established between local or regional self-governments – or interregional, in which cases the towns or larger territorial entities are not interconnected geographically, but work together based on a common interest. The members of these organizations are mostly in a similar situation in some way, usually in a disadvantaged position, and it is typical of them to form networks or umbrella organizations in more than one country. The most outstanding example is the Association of European Border Regions (AEBR) which was established for the first time in Europe in 1971 as the initiative of the border and cross-border regions, and its clear goal was to support cross-border forms of cooperation. Cross-border cooperation plays a significant role in strengthening previously coherent territorial units, in aligning border regions, and facilitating their involvement in the European process. However, these aims can only be achieved permanently if they appear in a common, institutionalized form. The importance of cooperation systems evolving along the external and internal borderlines of the European Union has been increasing since the last enlargements (in 2004 and 2007, 2013).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION

Legal framework - Council of Europe

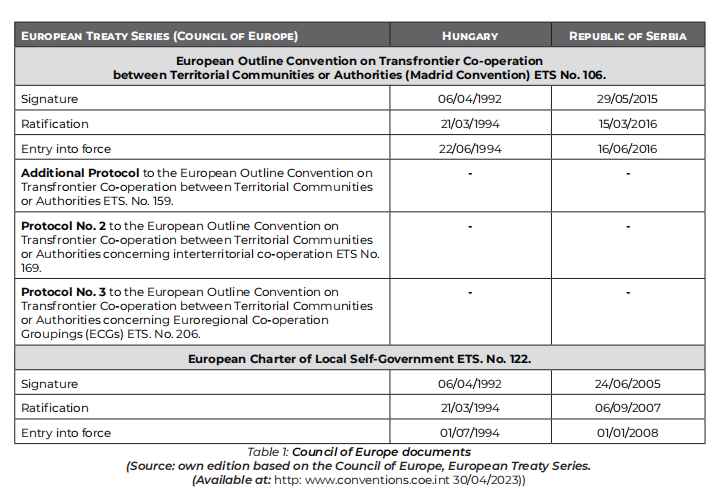

The Council of Europe has always recognized the crucial importance of democracy at both the local and regional levels. The Council of Europe has taken up a significant role in dismantling barriers to regional and international cooperation as well as strengthening cooperation across borders, with the aim of decentralisation. Numerous documents aiming to establish the legal framework for cross-border cooperation have been produced, including the Madrid Convention (1980) and the Additional Protocols (1995; 1998; 2009), the European Charter of Local Self-government and its Additional Protocol (1985; 2009), as well as the Council of Europe Reference Framework for Regional Democracy (2009).

At the European level, the only document that seeks to create comprehensive regulation on cross-border cooperation systems is the Madrid Convention, passed by the Council of Europe in 1980. The Convention plays a compensatory role, in which it defines the concept of cooperation across borders and offers patterns and proposals for the Member States to make the cooperation of regions and settlements across borders easier. The aim of the Convention is to promote cross-border agreements between local and regional authorities within the scope of their respective powers. Such agreements may cover fields such as regional, urban, and rural development, environmental protection, the improvement of public facilities and services and mutual assistance in emergencies, etc., and may include setting up transfrontier associations or consortia of local authorities. (Madrid Convention, Preamble).

In accordance with the Convention, transfrontier cooperation means any concerted action designed to reinforce and foster neighbourly relations between territorial communities or authorities within the jurisdiction of two or more Contracting Parties and the conclusion of any agreement and arrangement necessary for this purpose. Transfrontier cooperation takes place in the framework of territorial communities’ or authorities’ powers as defined in domestic law. (Madrid Convention, Article 2.) The specific forms of cooperation are derived from

the internal legal regulation of each Member State, according to the Convention, which only provides a legal framework that must be filled with specific content by the internal legislations of the ratifying Contracting Parties. The Convention must meet specific expectations, to be applied to the local and territorial relations of the ratifying Member States. Having variable legal and political systems, it must also create frameworks of bilateral and multilateral agreements. To allow for variations in the legal and constitutional systems in the Council of Europe’s Member States, the Convention sets out a range of model and outline agreements, statutes and contracts appended to itself,2 to enable both local and regional authorities as well as States to facilitate them with carrying out their tasks effectively.

The Convention has been modified several times, and three Additional Protocols (1995; 1998; 2009) were drafted. However, several recommendations and opinions of the international organisations representing regional interests (Council of Europe; Assembly of European Regions; Association of European Border Regions) only provide a framework for cooperation, which can be filled with the expected content only by national legal regulation.

2 Appendix numbered 1.1 to 1.5 and 2.1 to 2.6. These model and outline agreements, statutes and contracts are intended for guidance only and have no treaty value.

3 The three forms of EGTCs are: 1) cross-border cooperation between adjacent border regions in neighbouring countries; 2) trans-national cooperation between groups of countries and regions, mainly in the field of spatial planning; and 3) inter-regional cooperation between regions or cities in various countries.

4 Regulation (EC) No 1082/2006, Article 1. (4)–(5).

5 Ibid. Article 2. (1)).

6 Ibid. Article 3.2.

7 Ibid. Article 11. (1).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK - THE EUROPEAN UNION

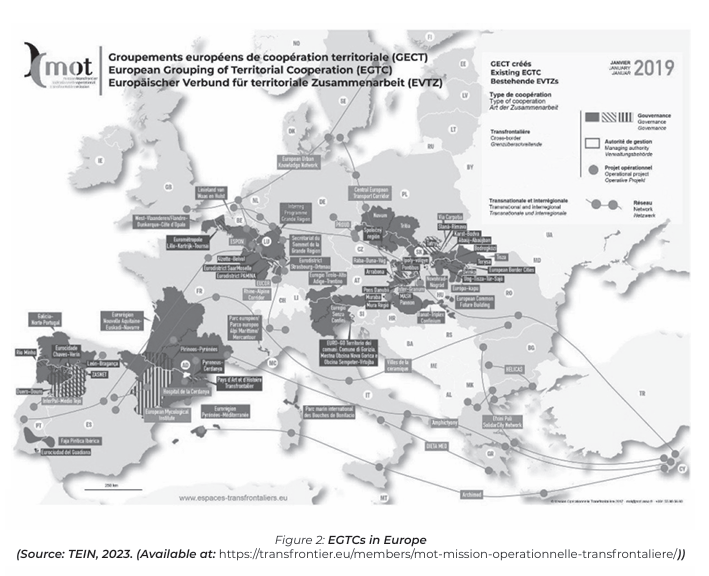

Over 25 years after the adoption of the Madrid Convention, Regulation (EC) 1082/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on a European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC) provides a response to the lack of legal and institutional instruments and ensures cooperation facilities for the local and regional authorities and Member States under EU law. The EGTC is a new European legal instrument that aims to facilitate and promote territorial cooperation, including one or more types of cross-border, transnational and interregional cooperation3 between its members with the aim of strengthening the Union’s economic, social, and territorial cohesion. (Regulation (EC) No 1082/2006, Article 1. (2)) The EGTCs have

legal personality, and are unique in the sense that they enable public authorities of various Member States to team up and deliver joint services without requiring a prior international agreement to be signed and ratified by national parliaments. (Maier, 2008: 37–40).

In each Member State the EGTC has the most extensive legal capacity accorded to legal persons under that Member State’s national law, and the registered office of the EGTC is located in a Member State under whose law at least one of the EGTC’s members is established.4 Where it is necessary to determine the applicable law under European Union law or private international law, the EGTC is an entity of the Member State where it has its registered office.5 With some exceptions, the members of EGTC can be states, local and regional authorities as well as other bodies and public undertakings – if they are located on the territory of at least two Member States.6 The EGTC establishes an annual budget which shall be adopted by the assembly, containing, especially a component on running costs and, if necessary, an operational component.7

However, the adaptation of the form of the EGTC is not obligatory; it is an instrument besides the existing ones, and choosing it is optional, it represents a new alternative to increase the efficiency, legitimacy, and transparency of the activities of territorial cooperation, and at the same time secures legal certainty. It is applicable in every Member State, even in those that have not signed the Madrid Convention and its Additional Protocols or the special bi- and multilateral agreements. The new legal instrument supplements the already existing initiatives

and forms of cooperation. (Ocskay, 2020: 48–54)

According to the Minister of Justice of Hungary,

The European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation embody in parallel

1. the solidarity and mutual respect of European nations whereby the national governments put their trust in an organisation established in another country; enabling them to realise developments and importantly, to provide services on the territory of the other state;

2. the reinforcement of European competitiveness when paving the way for joint development of peripheral regions previously separated by strictly protected administrative borders;

3. the European Union’s principle of subsidiarity – originating from Catholic Social Teaching – because the tool, in harmony with the model of multi-level governance, equally facilitates the participation of national, regional and local governments in institutionalised cross-border cooperation. (Varga, 2020: 3)

The EGTC signifies decentralized cooperation, and is built on years of experience with euroregional cooperation. Its vertical projection connects actors on different levels (European, national, sub-national) and involves them in the common European decision-making. On the other hand, its horizontal dimension leads to the interaction of actors on the same level, thus creating a European network whose operating principle is autonomy based on vertical and horizontal partnerships in accordance with multilevel governance (Medeiros, 2020:145–168; Scott, 2020:3763.; Soós, 2013: 519–531.) The multi-level governance platform is characterized by Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks as “task-specific governance”: the flexible structure

of a network with multi-level and cross-cutting membership aiming at delivering specific public goods for society. (2003: 6–12).

In 2013, the EGTC regulation was revised as regards the clarification, simplification and improvement of the establishment and functioning of such groupings (Regulation (EU) No 1302/2013). After that, several reports (Cross Border Review, Boosting Growth and Cohesion in EU Border regions, 2017) highlighted ways in which the EU and its Member States can reduce the complexity, length and costs of cross-border interaction and promote the pooling of services along internal borders. These looked at what needs to be improved to ensure that border citizens can take full advantage of the opportunities offered on both sides of the border.

Only six EGTCs were constituted during 2018 and 2019, which is relatively little compared with previous years. A few of the 75 EGTCs founded up until the end of 2019 are no longer active or were never operational. (CoR, 2020: 1–3) In 2018, the Commission adopted the European Cross-Border Mechanism (ECBM) legislative proposal to offer a legal tool for practical solutions to overcome cross-border obstacles of a legal or administrative nature. In 2019, to pioneer work to overcome these obstacles, the Commission launched alternate approaches, an innovative initiative that provides legal support to public authorities in border regions to identify the root causes of legal or administrative obstacles affecting their cross border interactions and to explore potential solution(s). This has been a successful process, which has resolved 90 cases of border obstacles. The cases covered 27 cross

border regions in 21 Member States and tackled obstacles mainly in employment, public transport, healthcare, and institutional cooperation. (COM/2021/393 final: 3).

According to the Commission Report in 2021 the COVID-19 pandemic emphatically demonstrated how interdependent EU Member States and regions are, how fragile internal borders can be, and how quickly we can lose the benefit of an open space with freedom of movement, albeit temporarily.

In many Member States, some of the f irst measures taken were to bring back internal border controls and ban access to their territories for neighbours who, in normal times, cross borders frequently for multiple reasons. The negative impact of these measures quickly became very visible in many border regions. It paralysed services, including healthcare facilities, because cross-border workers could not access their workplaces. Impediments to the free movement of goods disrupted supplies of much-needed medical equipment. Therefore, the recently adopted Strategy for an Area of Freedom, Security and Justice without internal borders takes due consideration of the experiences and lessons learnt from the COVID-19

pandemic. Furthermore, the Commission is in the early stages of preparing an amendment to the Schengen Borders Code which should address the identified shortcomings in the current system. (COM/2021/393 final: 1)

CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION IN HUNGARY

The economic and political changes of the 1990s in the countries of the Carpathian Basin show several features of the development of euro-regional cooperations that are different from the Western European models. After the change of the political system, the national movements and territorial conflicts revived in the Central and Eastern European region, which led to the emergence of new nation-states with specific legal and administrative structures. (Zachar, 2023: 109–193) While some nations (Czech, Slovak, Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian) reorganised their states as well, others (Polish, Hungarian, Romanian) only reformulated the foundations of their national identity. In order to allow the Hungarian border areas to become “building blocks” of the European cross-border cooperations, two conditions need to be met: the internal condition is the democratic development border regions taking part

in the cooperation, while the external one is compliance with the standards and frameworks established under the auspices of the Council of Europe: the Madrid Convention and its annexes outlining two types of cross-border cooperation opportunities: agreements between intergovernmental and local or regional authorities.

In the 1990s, Hungary signed most interstate treaties, the bilateral agreements on good neighbourly relations and friendly cooperation, which enabled most cross-border cooperations. In addition, Hungary convened bilateral interstate agreements on border cooperation with Ukraine and Slovakia, specifically based on the principles of the Madrid Convention, considering the circumstances of the two countries. (Government Decree No. 200/2001. (X. 20.) and Government Decree No. 68/1999. (V. 21.)) The importance of the bilateral intergovernmental agreements between Hungary and its neighbours lies in creating an opportunity to explore the experience and problems of lower-level cooperation organisations, joint committees as well as coordination forums established within these agreements, which guarantee holding the problems of the border areas on the agenda to ensure continuity.

Besides bilateral and multilateral interstate agreements established under international law, the support system of the 2007–2013 programming period provided a solution for the legal status of cross-border cooperations. The EGTC makes it possible for cross-border cooperation actors to develop uniform structures that have a legal personality and operate consistently under the law of the home member state. However, establishing an EGTC/ETT is optional, which means that the existing institutional structures will be retained. According to Article 16 of the EGTC Regulation, “Member States shall make such provisions as are appropriate to ensure the effective application of this Regulation.” Pursuant to this rule, Hungary adopted its national provisions in 2007 with Act XCIX on European Groupings for Territorial Cooperation (EGTC),8 among the first in the European Union, and the first EGTC in Central Europe – the Ister Granum – was established in 2008 with its seat at Esztergom in Hungary.

The European Committee of the Regions regularly publishes a Monitoring Report on the development of the European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation. According to the EGTC register (CoR, 2023), in 2023, EGTCs included more than 800 national, local and regional authorities from 20 different Member States and from Ukraine. The last four EGTC Monitoring Reports found that EGTCs focused on Central and Eastern European territories had been established. The dominant type of partnership is composed of local authorities: half of all groupings are powered by the local level. The second largest group comprises EGTCs of regional authorities, with the number of partners ranging between two and six. Half of the recently constituted EGTCs are following this trend, covering territories in Hungary, Romania, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. (CoR, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020). There are currently 25 EGTCs registered in Hungary, 3 of which headquarters in Slovakia Karszt–Bódva EGTC, Pons Danubii EGTC, and Via Carpatia EGTC), 1 in Poland (Central European

Transport Corridor Limited Liability European Grouping of Territorial Co-operation, headquarter in Szczecin) and 21 in Hungary.

8 The EGTC Act was modified by Act LXXV of 2014 and 2/2014. (XII.30.) MFAT decree of the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade on the detailed rules concerning the approval and registration proceedings of the EGTCs. The Hungarian name for the European grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) became “európai területi társulás” (European Territorial Association, or ETT).

HORIZONTAL DIMENSION OF CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION

Besides EGTCs, the horizontal dimension and the functional macro-regions are increasingly emphasised in the EU’s cohesion policy. Macro-regional cooperations (such as the EU Duna Region Strategy) are initiated by the European Union. These require not only the specification of the mutual aims and the relevant equipment, but also the development of new methods of governance and mechanisms that would ensure a coherent framework to join the interregional, transnational and border regional agreement networks. The Danube Strategy is a new framework and opportunity for deepening multi-level governance, which coordinates internal and external relations previously managed separately. Therefore, the concept of governance appears not only on global and national levels, but as a result of networking, the concept will embrace regulatory strategies and projects. Their task is to strengthen cooperation and coordination between the lower-level governments, as well as in the relations of public and private institutions and actors.

In Europe, one of the most renewable and constantly changing areas is the Danube region, which is approximately 2,840 kilometres along the banks of the Danube river, whose catchment area is home to 115 million inhabitants, from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. The Danube connects people living in its valley not only in a geographical sense, but it also provides an opportunity for cooperation, in which a significant role is played by local and regional self-government actors as well as the states. The question of national, regional, and local identity, the problem of borders separating and connecting people, the possibility of cooperation of the regions belonging to each other economically as well as the connections between people, their ideas and needs are all inherent in this unity. (Fejes, 2011: 105–112).

Another horizontal cooperation, the Central European regional Visegrád Cooperation, sought to create a new form of cooperation both in the political, economic and cultural spheres in order to focus on the transition to democracy, to promote the modern market economy and to implement the Euro-Atlantic – EU and NATO – access. Later, the four countries reaffirmed their determination to continue mutual cooperation to achieve a strong, stable, and democratic Europe. In addition, they intended to form a common position on a global level concerning the issue of peace and sustainable development. The V4 Group’s renewed cooperation thus endeavours to safeguard their common historical and economic interests, i.e.

that the V4 group will be able to effectively represent the interests of Central Europe in the future and the four countries together can constructively contribute to the success of the European Union. (Mészáros, Halász, Illés: 2017).

By now, all V4 countries have had a turn hosting the Council of the European Union’s rotating presidency, and no one can question the added value of its members and the community in this region of Europe. And even though the success of this region is our primary common interest, this can only be reached by revealing the legal barriers blocking everyday life which significantly restrict crossborder development organisations’ capacity to act. The V4 was not created as an alternative to pan-European integration efforts, nor does it try to compete with

existing functional Central European structures. The backbone of this cooperation consists of mutual contacts at all levels – from the highest-level political summits to expert and diplomatic meetings, to activities of the non-governmental associations in the region, think-tanks and research bodies, cultural institutions, or numerous networks of individuals. (Böhm et al, 2018; Soós, 2015: 39).

EXTERNAL DIMENSION OF CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION: THE HUNGARIAN-SERBIAN BORDER

References

2. Fejes, Zsuzsanna (2011): Fejes, Zsuzsanna. A Duna-stratégia a többszintű kormányzás rendszerében; Európai Tükör, vol. 16, no. 1; 105–112.

3. Hardi, Tamás (2004): Az államhatárokon átnyúló régiók formálódása. [Forming Regions across the State Borders]; Magyar Tudomány, no. 3, http://www.matud.iif.hu/04sze.html

4. Hooghe, Liesbet and Gary, Marks (2001): Multi-Level Governance and European Integration; Oxford: Rowman-Littlefield Publishers, 2001.

5. Hoogh, Liesbet and Marks, Gery (2003): Unraveling the Central State, But How? Types of Multi-Level Governance; Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies, Political Science Series 87, 6–12.

6. Böhm, Hynek et al. (2018): Proposal on the V4 Mobility Council as intergovernmental structure for border obstacle management; Budapest: CESCI.

7. Kaiser, Tamás (2014): New Forms of Governance in Transnational Cooperations; Pro Publico Bono, vol. 2, no. 3; 53–60.

8. Keating, Michael (1998): The New Regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial Restructuring and Political Change; Edward Elgar Publishing; 1st edition.

9. Maier, Johannes (2008): European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) – Regions’ new instrument for ‘Co-operation beyond borders’. A new approach to organise multi-level-governance facing old and new obstacles; Bolzano–Luxembourg–Graz–Barcelona: M.E.I.R., 37–40.

10. Medeiros, Eduardo (2020): The EGTC as a tool for cross-border multi-level governance; In: Ocskay, Gyula (ed.): 15 years of the EGTCs. Lessons learnt and future perspectives; Budapest: CESCI; 145–168.

11. Mészáros, Andor – Halász, Iván – Illés, Pál Attila (2017): Visegrádi kézikönyv: Történelem – politika – társadalom; Esztergom: Szent Adalbert Közép- és Kelet-Európa Kutatásokért Alapítvány.

12. Nárai, Márta – Rechnitzer, János (eds.) (1999): Elválaszt és összeköt – a határ: társadalmi és gazdasági változások az osztrák–magyar határ menti térségben. [Separation and Connection – the Border: Social and Economic Changes in the Austrian–Hungarian Border Region]; Győr–Pécs: MTA Regionális Kutatások Központja.

13. Newman, David (2019): Managing Borders in a Contrasting Era of Globalization and Conflict; In: Gyelník, Teodor (ed.): Lectures on cross-border governance: Situatedness at the border; Budapest: CESCI; 91–112.

14. Ocskay, Gyula (2020): Changing interpretation of the EGTC tool; Ocskay, Gyula (ed.): 15 years of the EGTCs. Lessons learnt and future perspectives; Budapest: CESCI; 48–62.

15. Paasi, Anssi (2019): Bounded spaces challenged – regions, borders, and identity in a relational world; In: Gyelník Teodor (ed.): Lectures on cross-border governance: Situatedness at the border; Budapest: CESCI; 69–90.

16. Perkmann, Markus (2002): Policy entrepreneurs, multilevel governance, and policy network in the European policy: The case of the EUROREGIO; Department of Sociology, Lancaster University.

17. Peyrony, Jean (2020): Underlying visions of cross-border integration; In: Ocskay, Gyula (ed.): 15 years of the EGTCs. Lessons learnt and future perspectives; Budapest: CESCI; 219–242.

18. Scott, James (2019): New approaches to understand and assessing crossborder cooperation; In: Gyelník, Teodor (ed.): Lectures on cross-border governance: Situatedness at the border; Budapest: CESCI; 45–68.

19. Scott, James Wesley (2020): The European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation as a Process of Europeanisation; In: Ocskay, Gyula (ed.): 15 years of the EGTCs. Lessons learnt and future perspectives, Budapest: CESCI; 63–80.

20. Soós, Edit (2013): Contribution of EGTCs to Multilevel Governance; International Journal of MuItidisciplinary Thought, vol. 3, no. 3; 519–531.

21. Soós, Edit (2015): New modes of governance. In: Wiszniowski, Robert – Glinka, Kamil (eds.): New Public Governance in the Visegrád Group (V4). Torun: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszalek; 35–49.

22. Telle, Stefan (2017) Euroregions as soft spaces: between consolidation and transformation; European Spatial Research and Policy, vol. 2, no. 2; 93–110.

23. Zachar, Péter Krisztián (2023): Transition, Participation and Self-Governance: The Institutional Change of Hungarian Chambers; Budapest: Ludovika Egyetemi Kiadó.

24. Zillmer, Sabine et al. (2018): EGTC Good Practice Booklet; Brussels: European Committee of the Regions, 30/07/2018.

OTHER SOURCES

1. AEBR (2011): European Charter for Border and Cross-border Regions; Gronau: Association of European Border Regions; 15 September 2011.

2. AEBR-EC (2000): Practical Guide to Cross-border Co-operation; Guide, AEBR–European Commission, 3rd edition.

3. BTC EGTC (2023): Banat–Triplex Confinium EGTC website, https://www.btc-egtc.eu/

4. CESCI Balkans (2017): Legal Accessibility Serbia’s Participation in European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) and Euroregional Cooperation Grouping (ECG) Novi Sad: CESCI, 2017.

5. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament “Boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions” {SWD(2017) 307 final}

6. CoR (2009): The European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC): state of play and prospects; Brussels: Committee of the Regions, 2009.

7. CoR (2016): EGTC Monitoring Report 2015 Implementing the new territorial cooperation programmes. Brussels: Committee of the Regions.

8. CoR (2017): EGTC monitoring report 2016 and impacts of Schengen area crisis on the work of EGTCs; Brussels: Committee of the Regions.

9. CoR (2018): EGTC monitoring report 2017, Brussels: Committee of the Regions.

10. CoR (2020): EGTC monitoring report 2018–2019, Brussels: Committee of the Regions, Commission for Territorial Policy and EU Budget (COTER).

11. CoR (2023): List of the Groupings of Territorial Cooperation. Brussels: European Committee of the Regions. 10.03.2023.

12. Cross-border Review. Brussels: European Commission, 2017. http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/cooperation/european-territorial/cross-border/review/

13. DKMT Euroregion (2023): The Danube–Kris–Mures–Tisa Regional Cooperation. DKMT website, http://www.dkmt.net/en/index.php?bov=61361200392410

14. European Outline Convention on Trans-frontier Cooperation between Territorial Communities or Authorities, Madrid, 21 May 1980 (in force, 22 December 1981) Council of Europe, ETS No. 106.

15. INTERACT (2008): Handbook on the European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC). What Use for European Territorial Cooperation Programmes and Projects; Vienna: INTERACT Point.

16. MOT (2008): Guide on The European grouping of territorial cooperation; Paris: Mission Operationnelle Transfrontalière, May 2008.

17. Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on a mechanism to resolve legal and administrative obstacles in a cross-border context COM/2018/373 final – 2018/0198 (COD)

18. Regulation (EC) No 1082/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on a European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC) OJ L 210, 31.7.2006, 19–24.

19. Regulation (EU) No 1302/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 1082/2006 on a European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC) as regards the clarification, simplification and improvement of the establishment and functioning of such groupings OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, 303–319.

20. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the European Committee of the Regions: EU Border Regions: Living labs of European integration COM/2021/393 final. Brussels, 14.7.2021.

21. The Committe of the Regions’ White Paper on Multilevel Governance. CoR, Brussels, 17–18/06/2009. CdR 89/2009 fin.

22. White Paper on European governance. European Commission, Brussels, 12.08.2001. COM (2001) 428 fin.

Published in

Volume 3, Issue 5, 2023

Keywords

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals