Local Authorities at the Forefront of Climate Policy

Abstract

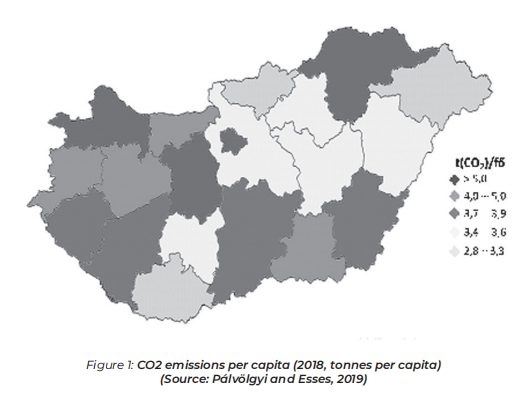

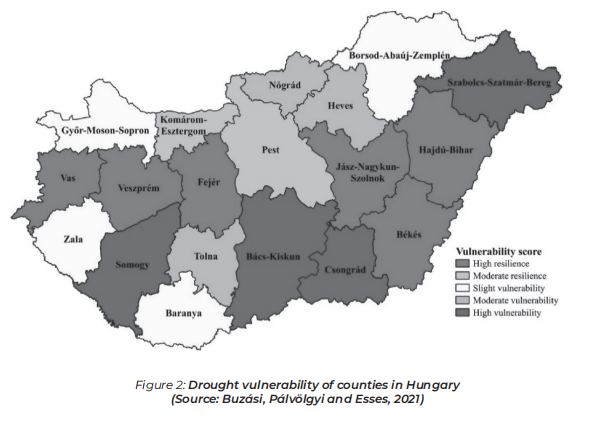

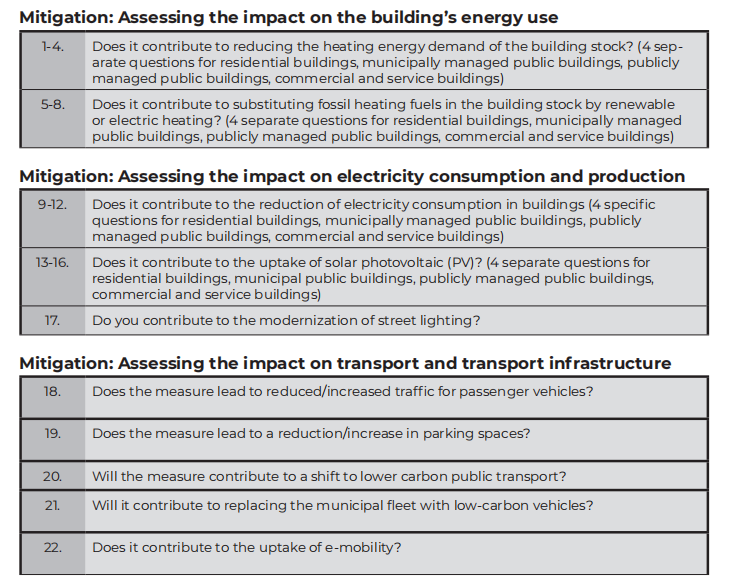

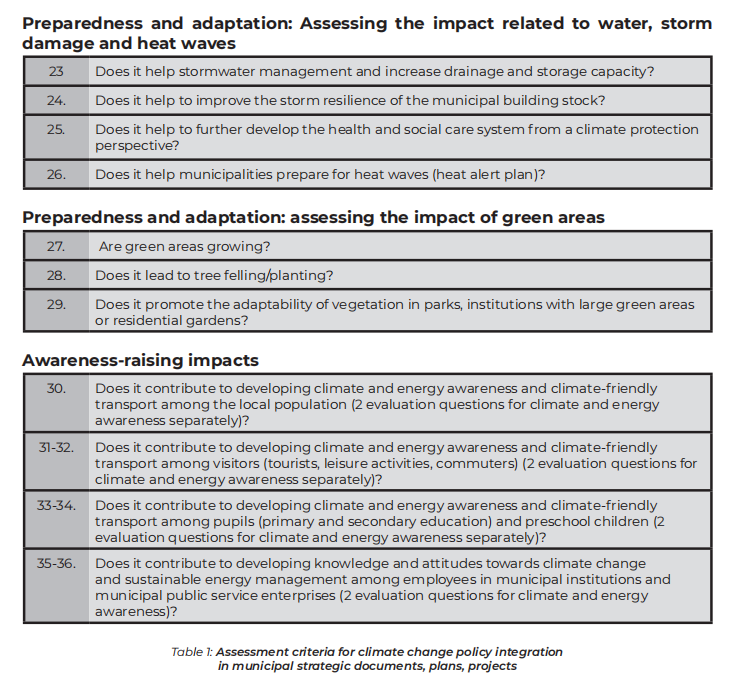

Preparing for and adapting to the impacts of climate change depends fundamentally on local communities, whether in a large city or a small rural area. In many cases, activities, measures and interventions related to mitigation and adaptation are difficult to implement without social cooperation. Today, it is becoming increasingly clear that climate policy measures can be seen as a key to the future success of municipalities. In this paper, we review the strategic basis for municipal climate policies and present a case study of Hungary to illustrate how municipalities’ decarbonization performance can be measured and evaluated. We then present a crucial element of climate adaptation at the municipal level, the vulnerability assessment of drought risk at the county level. We will analyse the municipal adaptation options and then review urban development projects’ climate performance assessment methodology. In the context of municipal climate policy integration, we present a preliminary climate impact assessment methodology for municipal legal and strategic documents. Finally, in conclusion, we summarise the success factors of municipal climate strategies and make recommendations for the implementation of municipal climate strategies.

Article

INTRODUCTION

References

2. Buzási A., Pálvölgyi T. and Esses D. (2021). Drought-related vulnerability and its policy implications in Hungary. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 26, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-021-09943-8

3. Buzási A., Szimonetta Jäger B., Hortay O. (2022). Mixed approach to assess urban sustainability and resilience - A spatio-temporal perspective. City and Environment Interactions, Volume 16, 100088, ISSN 2590-2520, doi.org/10.1016/j.cacint.2022.100088.

4. IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

5. Pálvölgyi, T., Czira, T., Fancsik, T. (2016). Applying science-based decision-preparatory information in “climate-proof” public policy planning. In: Knowledge Sharing, Adaptation and Climate Change. Research and Development Results of the Hungarian Geological and Geophysical Institute for the Establishment of the National Adaptation Geoinformatics System. Eds. T. Pálvölgyi and P. Selmeczi Hungarian Geological and Geophysical Institute, Budapest.

6. Pálvölgyi T. and Esses D. (2019). Regional characteristics of greenhouse gas emissions and decarbonization options in Hungary. DETUROPE - THE CENTRAL EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND TOURISM, Vol. 11 Issue 3 2019 ISSN 1821-2506.

WEBOGRAPHY

1. Wamsler C, Brink E., Rivera C. (2013). Planning for climate change in urban areas: from theory to practice, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 50, 2013, Pages 68-81, ISSN

0959-6526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.008.

2. ACFM, 2018: Guidance for the development of climate strategies for municipalities Association of Climate Friendly Municipalities - Hungarian Mining and Geological Survey (KEHOP-1.2.0-15-2016-00001, “Provision of technical support and coordination in local climate strategies”) http://klimabarat.hu/images/tudastar/8/kepek/KBTSZ_modszertanfejl_VaROS_180226.pdf

Published in

Volume 3, Issue 5, 2023

Keywords

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals