Mistaken Theses in the Debate on Deindustrialization and Loss of Competitiveness of Brazilian Industry

Submission received:

21 November 2024

/

Accepted:

4 December 2024

/ Published:

30 December 2024

Abstract

Nowadays it is a consensus among Brazilian economists that Brazil suffered a huge process of deindustrialization since 2005. But this consensus had emerged only in the last years. During the period between 2008 and 2012 a huge debate between heterodox and orthodox economists in Brazil occurred about the existence of deindustrialization. The orthodox economists had denied the existence and/or the relevance of deindustrialization for the Brazilian economy for many years. At the end, they lost the debate, heterodox economists, mainly the ones related with the so-called the Brazilian new-developmentalist School were right: Brazil deindustrialize, and this negative structural change had reduced the long-term growth of Brazilian economy. The objective of this paper is to present the orthodox thesis about the deindustrialization of Brazilian economy, identifying the reasons by which they proved to be wrong. As we shall argue on this article, deindustrialization in Brazil is not a natural outcome of development process, but it is premature and caused, mainly, by exchange rate overvaluation that is the result of the increase in terms of trade occurred in the period between 2005 and 2011. Moreover, deindustrialization is not an irrelevant phenomenon for development of Brazilian economy in medium and long-term, since manufacturing industry is a unique sector where we observe the highest levels of labour productivity.

Article

INTRODUCTION

In the economic literature, the term deindustrialization has been used to explain the relative loss of industrial employment in developed countries since 1970. For Tregenna (2009), the most appropriate concept would be a persistent relative loss of both employment and value added. In addition, deindustrialization is followed by strong growth in the service sector, including total exports1. Sometimes the process of deindustrialization is also associated with the problem of ‘Dutch disease’2. According to Rowthorn and Ramaswamy (1999), in the dynamics of development, deindustrialization can be seen as a natural phenomenon, because as countries consistently increase per capita income, the income elasticity of demand for industrialized products decreases, which leads to a relative reduction in demand for industrialized products. In addition, strong productivity growth in the industrial sector leads to a fall in the relative prices of industrial goods, thus leading to a reduction in the manufacturing sector’s share of value added and total employment3.

Regarding the long-term effects of the deindustrialization process, Oreiro and Feijó (2010) and Tregenna (2009) argue that deindustrialization is seen as a problem for the growth of capitalist economies by the heterodox literature à la Kaldor, since in the orthodox perspective the sectoral composition of production is not relevant to economic growth. According to Kaldor (1967), manufacturing industry is the engine of long-term growth due to four fundamental characteristics of the manufacturing sector, namely: i) presence of increasing returns to scale; ii) higher forward and backward linkages in the production chain; iii) creates and diffuses technological progress and iv) have a greater income elasticity of exports. In this context, a process of deindustrialization reduces long-term potential growth.

Palma (2005) points out four explanations for deindustrialization: i) reallocation of industrial labour to services due to growing outsourcing; ii) reduction of the income elasticity of demand for manufactured goods; iii) high productivity growth in industry driven by ICTs and iv) a new international ‘division’ of labour. About the last aspect, we could call it a growing specialization resulting from North-South trade4. These arguments converge not only with Kaldor’s ‘stylized facts’, but also with Rowthorn and Ramaswamy’s (1999) explanations for deindustrialization. In the case of Brazil and the countries of the Southern Cone, the author draws attention, however, to external shocks or structural changes as drivers of premature deindustrialization.

Nassif (2008) points out that, although there is no consensus on the occurrence of deindustrialization in the Brazilian case, the literature has sought to explain the process of deindustrialization because of both the import substitution model, the process of trade liberalization and overvaluation exchange rate policy combined with the rise in relative price of commodities. However, he concludes that the reduction in the share of manufacturing industry in the GDP occurred in the second half of the 80s, even before structural changes, such as the opening of trade and the stabilization process and is mainly due to the strong drop in labour productivity in this period. In the 90s, the scenario was different with the increase in productivity and a drop in investment rates, the author points out.

It is worth emphasizing, however, that from 1999 onwards labour productivity in Brazil assumed an unstable behaviour, but with higher levels than in the early 90s. Investment also presents some instability and with a downward trajectory in the 90s, reaching the lowest level in the last quarter of 1999 (14.7% of GDP). In the first quarter of 2000, investment had a strong growth, but continued with a downward trend, whose recovery only occurred from 2004 onwards and reached a higher level in the third quarter of 2008. With the global financial crisis, which had its worst moment in the last quarter of 2008, investment suffers a drop of about two percentage points. The output and relative employment in industry also dropped, but the biggest reduction was seen in the productivity of the industry.

In this context, Nassif (2008) opposed to the deindustrialization thesis point out that the relative loss of industry in employment and total output is the result of the lack of a favourable macroeconomic environment for the resumption of growth than an effective deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy. This is one of the arguments of Bonelli and Pessoa (2010) that reinforce the idea that the evidence, in the Brazilian case, regarding the thesis of deindustrialization is not conclusive. For these authors, it would be necessary to distinguish three aspects: i) whether the relative reduction of manufacturing industry is associated with macroeconomic instability; ii) whether there is a worldwide trend of relative loss of manufacturing industry from global production and iii) whether there is a persistent decline in manufacturing activity. Considering these aspects, the authors point out that the loss of the industry’s participation was not so intense and occurred mainly in the period prior to 1993, a phase in which the Brazilian economy and the world economy went through external crises and

macroeconomic instability.

Bresser-Pereira and Marconi (2008), in turn, argue that deindustrialization in Brazil is the result of the ‘Dutch disease’. They claim that the simultaneous occurrence of an overvalued exchange rate and trade imbalance of the manufacturing would be proof of the existence of ‘Dutch disease’ in Brazil. The authors also highlight the change in economic policy initiated in the 90s, favouring this scenario5. From the point of view of foreign trade, the authors state that the process of trade opening provided not only an increase in imports, but favoured the increase in exports (new consumer markets).6 Regarding exchange rate policy, the authors’ argument is that the reduction in the real exchange rate, the increase in external demand, combined with the increase in relative commodity prices and the growth of the world economy contributed to the boom in Brazilian exports until 2007. Despite this favourable result in the trade balance, the central issue is the effect of an overvalued exchange rate on industrial production. The authors point to a discouragement of production in less competitive sectors7. From this perspective, an overvalued exchange rate may contribute to a ‘Dutch disease’ scenario because even if there is no discovery of new natural resources, there would be a tendency towards the specialization of exports of primary or manufactured products intensive in natural resources and labour, favoured by the exchange rate policy8.

The analysis of the recent Brazilian literature about deindustrialization seems to leave little room for doubt about the effective occurrence of this process (Oreiro and Feijó, 2010; Oreiro, D´Agostini and Gala, 2020). In fact, once the usual definition of deindustrialization is accepted as a process in which there is a reduction in the share of value added in industry in GDP and/or industrial employment in total employment, it becomes unquestionable that this process has been occurring in Brazil, with greater or lesser intensity, in a linear way or not, since the end of the 1980s.

In the debates on deindustrialization and the competitiveness of Brazilian industry, that occurred mainly between 2008 and 2012, economists of orthodox theoretical matrix have presented a series of arguments in the sense of denying the occurrence of the phenomenon of deindustrialization or minimizing the effects of this phenomenon on the long-term growth potential of the Brazilian economy. These arguments, although not always compatible with each other, constitute a set of ten theses regarding the situation of Brazilian industry at that

time. Based on these theses, deindustrialization – if effective – would be a natural consequence of the development process of the Brazilian economy, that is, of the increase in the income elasticity of the demand for services that is induced by the growth of per-capita income; and aggravated by the low dynamism of labour productivity, resulting from the semi-autarkic nature of the Brazilian economy. In this context, real wages tend to grow above labour productivity, thus increasing the unit cost of labour in national currency, which leads to a growing deterioration in the competitiveness of manufacturing industry. The observed overvaluation of the real exchange rate observed between 2005 and 2012 would be a secondary -

that is, not a fundamental - reason for the loss of competitiveness of industry; but it would be related to the very logic of the Social Welfare State implanted de jure in Brazil with the 1988 Constitution and de facto with the two terms of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Thus, the restoration of the competitiveness of industry through the devaluation of the exchange rate would be something unfeasible from the political point of view. Finally, it is argued that deindustrialization, even if irreversible, would not have negative effects on the growth potential of the Brazilian economy, because manufacturing industry is a sector like any other, not being fundamental for a sustained increase in per-capita income in the medium and long term.

That said, this article aims to present the theses of orthodoxy on the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy, pointing out the reason why they are mistaken. As we will argue throughout this article, Brazilian deindustrialization is not a natural consequence of the development process, being of premature nature and caused, above all, by the exchange rate appreciation overvaluation caused by the appreciation of the terms of trade observed between 2005 and 2011. In addition, deindustrialization is not an irrelevant phenomenon on the development of the Brazilian economy in the medium and long term, since manufacturing industry is not a sector like any other, but it is the sector where the highest levels of labour

productivity are observed.

1 See Rowthorn and Wells (1987).

2 The term ‘Dutch disease’ refers to a process of premature deindustrialization, as occurred in the Netherlands in the 70s when there was a ‘reprimarization’ of exports, resulting from the discovery of natural resources [Nassif (2008)].

3 Given the various concepts of deindustrialization, Oreiro and Feijó (2010) call attention to the fact that deindustrialization is not necessarily a bad thing. The relative drop in the participation of manufacturing industry in output and employment may be accompanied by an increase in the participation of products with higher technological content and added value in the export basket. However, it is worth noting that this is not the case in Brazil.

4 The ‘stylized fact’ evidenced in the North-South models is the greater income elasticity of the demand for imports to the countries of the South compared to those of the North, which explains the uneven development [Dutt (2003)]. These models also refer us to the ideas of the Ricardian theory trade model and to ECLAC’s thinking of deterioration of the terms of trade.

5 The country has moved from a regime of tariff and exchange rate control markedly from an ISI model to a policy of trade openness and a floating exchange rate regime.

6 Since 2002, the country has been accumulating a positive balance of trade and it is only after the 2008 crisis that this situation begins to be reversed. Moreira (1999) points out that the process of trade liberalization favoured, mainly, imports in sectors that were intensive in technology and, in exports, those that were more intensive in natural resources or little intensive in technology and capital.

7 Rowthorn and Ramaswamy (1997) call attention to an aspect that is rarely mentioned about the effects of exchange rate appreciation. Certainly, in this context, an additional symptom for the verification of ‘Dutch disease’ should be associated with the growth of unemployment in the economy. Because if deindustrialization is not a natural process, then the service sector would not be able to absorb this labour liberated from industry.

8 This debate about the behaviour of the exchange rate and the possibility of specialization of the structure of exports has gained space in the economic scenario mainly from the discovery of the pre-salt layers.

THESIS ON DEINDUSTRIALIZATION AND LOSS OF COMPETITIVENESS OF BRAZILIAN INDUSTRY

An analysis of the arguments presented by the orthodoxy in the debate on the deindustrialization and loss of competitiveness of the Brazilian economy allows us to list the following set of Theses:

1. Deindustrialization is a worldwide phenomenon.

2. The Brazilian economy is not deindustrializing.

3. Brazilian deindustrialization is a natural consequence of its stage of development

4. Manufacturing industry is a sector like any other.

5. Brazilian deindustrialization is not due to the overvaluation of the exchange rate.

6. The exchange rate appreciation in Brazil is like that of other emerging countries.

7. The loss of competitiveness of Brazilian industry is due to the low dynamism of productivity and wage growth.

8. The exchange rate overvaluation is a result of the implementation of the “Social Welfare State”.

9. The overvalued exchange rate in Brazil is a permanent phenomenon.

This set of theses does not constitute an internally consistent set of propositions as they reflect the position of several representatives of Brazilian orthodoxy. In fact, while some representatives of orthodoxy simply deny the occurrence of the phenomenon of deindustrialization (Thesis 2); others accept the occurrence of the same (Thesis 1 and 3), but minimize the impact of this phenomenon on the long-term growth of the Brazilian economy (Thesis 4 and 5) or consider that such a phenomenon is irreversible, resulting from the de facto implementation of the Social Welfare State in the Brazilian economy during the two terms of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and the low growth of labour productivity resulting from

the semi-autarkic character of the Brazilian economy9.

The theses listed above point to the idea that deindustrialization evidenced by the Brazilian economy (disregarding Thesis 2) is a natural result of its development process, that is, resulting from the increase in the income elasticity of the demand for services that is induced by the increase in the level of per-capita income. In this context, the deindustrialization that occurred in the Brazilian economy would reflect a phenomenon that occurs on a global scale, that is: the loss of importance of industry in the total employment and GDP of the various countries. It is admitted, however, that the deindustrialization that occurred in Brazil may be deeper than that observed in the rest of the world due to the semi-autarkic character of the Brazilian economy, which translates into productive inefficiency and low dynamism of labour productivity10. In this context, real wages grow faster than labour productivity, thus

leading to a sharp increase in the unit cost of labour and, consequently, to a sharp reduction in the competitiveness of Brazilian industry.

The overvaluation of real exchange rate observed since 2005 (Oreiro, D´Agostini and Gala, 2020) may accentuate this loss of competitiveness, but it is not its main cause. This is because the exchange rate appreciation verified in Brazil would be like that observed in other emerging countries, in such a way that the relative competitiveness of the Brazilian economy would not have been seriously affected by it. In addition, the exchange rate appreciation observed since 2005 would be of a permanent nature, which would make any attempt to correct the problem of loss of competitiveness through an adjustment of the real exchange rate unfeasible. In fact, it is argued that the exchange rate overvaluation results from the strong appreciation of the terms of trade of the Brazilian economy from 2005 to 2011 (Bacha, 2024), due to the economic growth of China, and the de facto implementation of

the Social Welfare State in Brazil during the two terms of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, which would have led to an increase in the price of non-tradeable goods with respect to tradeable goods.

Finally, it is argued that deindustrialization would have no significant effect on the long-term growth prospects of the Brazilian economy because not only manufacturing industry is one sector but also another; and, moreover, Australia’s historical experience shows that the existence of a robust industrial sector is not essential for long-term economic development.

9 Some exponents of one or more of these theses are Pessoa (2011) and Ferreira and Frageli (2012).

10 The same argument is presented recently by Bacha (2024)

DID BRAZILIAN ECONOMY DEINDUSTRIALIZE?

To answer this question clearly, we must precisely define the meaning of the term deindustrialization. As we argued in the introduction to this article, deindustrialization is defined as a process of a structural nature in which the share of manufacturing industry in employment and GDP is consistently reduced over time. As highlighted by Oreiro and Feijó (2010), deindustrialization may or may not be accompanied by a re-primarization of exports, the occurrence of the latter only reinforces the negative character of the former.

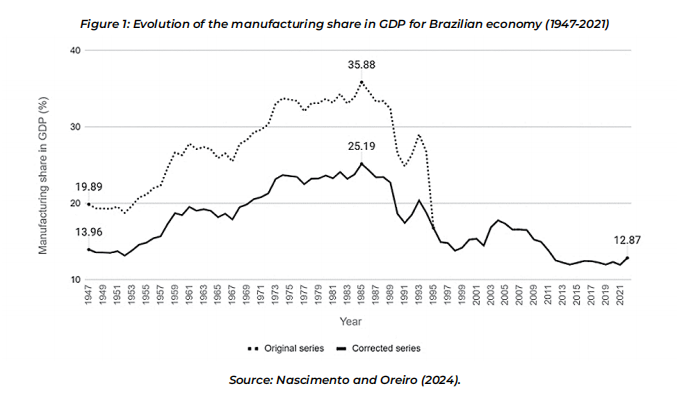

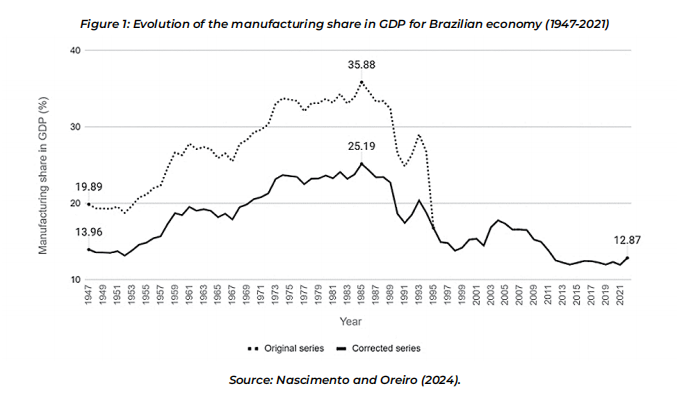

There is also a difficulty in determining the occurrence of deindustrialization process from the mid-1990s onward, as there were methodological changes in GDP calculation implemented by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2007, making it impossible to compare the industry’s value-added share in GDP series in the periods before and after 1995 (Oreiro and Feijó, 2010). However, the data series provided by IBGE regarding the share of the industrial sector in the total GDP can be adjusted to be comparable, and it clearly indicate the occurrence of deindustrialization after 1995.

It was possible to correct the IBGE series by using the database provided by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (Ipeadata) and applying the same methodology as Bonelli and Pessôa (2013), in which they used the percentage variations of the nominal values from the old systems and retroactively applying these rates to the 1995 result. After that year, the two series (original and corrected) coincide. As shown in the Figure 1 below, the corrected series is still indicative of deindustrialization, even up to 2022. While the millennium began with approximately 15.37% of the manufacturing industry’s share in the total Brazilian GDP, 21 years later, this share was reduced by 2.5 percentage points, representing only 12.87% of the

GDP in 2022. Its highest point was 25.19% in 1985, while the lowest was 11.97% in 2021. There was a decrease of approximately 12.3 percentage points in the manufacturing

share in total GDP between the years 1985 and 2022.

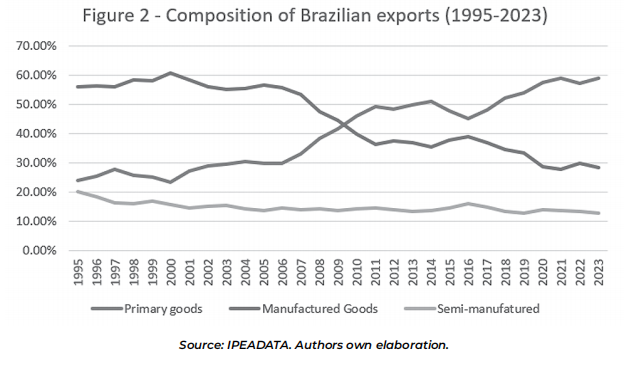

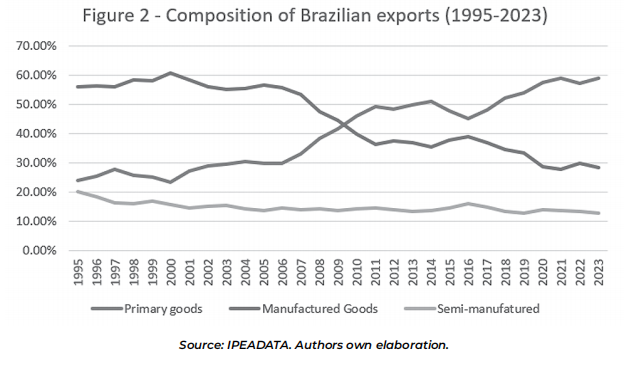

This movement of loss of the manufacturing share in value added has been accompanied by a change in the composition of exports since 2005. In fact, as we can see in figure 2 below, the share of manufactured products in the export basket began to show a strong downward trend from 2005 onwards, having been surpassed by the share of primary products in 2009. Based on these data, we can say that Brazil has returned to being a primary-exporting economy.

IS DEINDUSTRIALIZATION A GLOBAL PHENOMENOMENON?

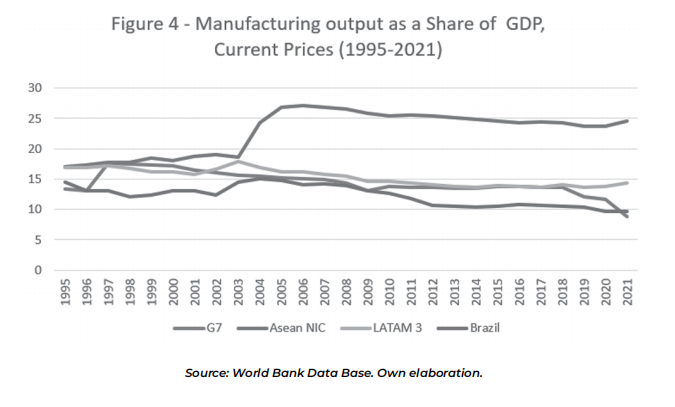

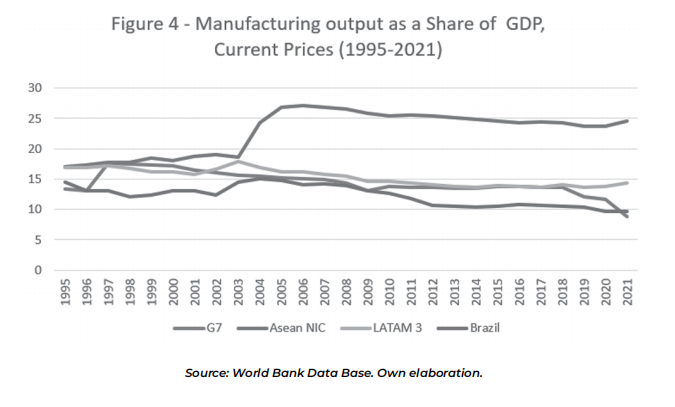

It is not true that deindustrialization is a worldwide phenomenon. As we can see in figure 4 below, while the share of manufacturing industry in GDP has been decreasing in the G7 countries and in the three biggest Latin American economies (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico) since, at least, 1995; but in the New Industrialized Countries (NIC) of Asia (China, South Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia) in the dynamic countries of Asia, it increased at almost 7 pp. of GDP from 2004 on and stabilize at a level of 25% of GDP in 2021. Thus, what has been observed worldwide is not the loss of importance of manufacturing industry, but a change in its spatial location from the West to the East, notably Asia.

IS BRAZILIAN DEINDUSTRIALIZATION A NATURAL CONSEQUENCE OF ITS STAGE OF DEVELOPMENT?

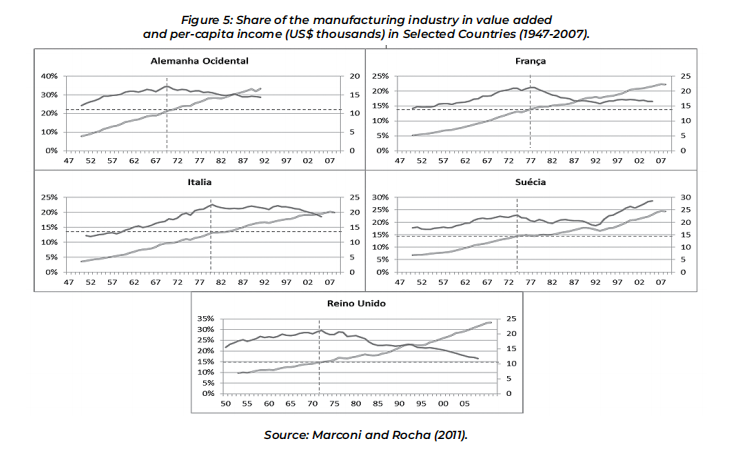

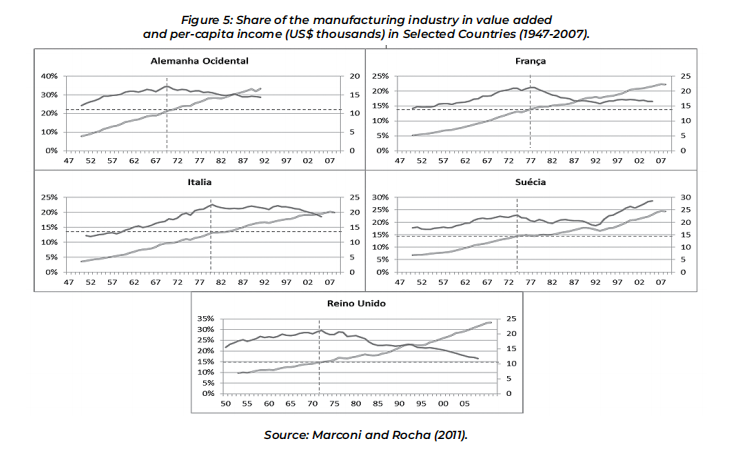

The term premature deindustrialization was originally created by Palma (2005) to represent a situation in which the share manufacturing of industry in employment and/or in the value added of a given country begins to be reduced to a level of per-capita income lower than that verified in developed countries when they began their deindustrialization process. As we can see in figure 5 below, deindustrialization in developed countries began in the first half of the 1970s with a per-capita income level between 10 and 15 thousand dollars.

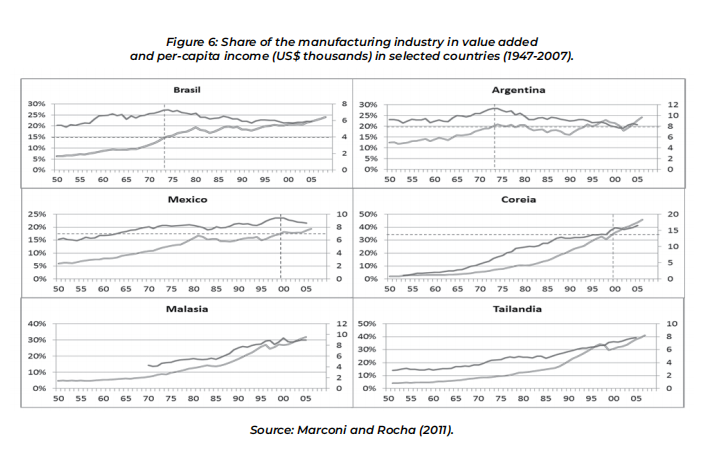

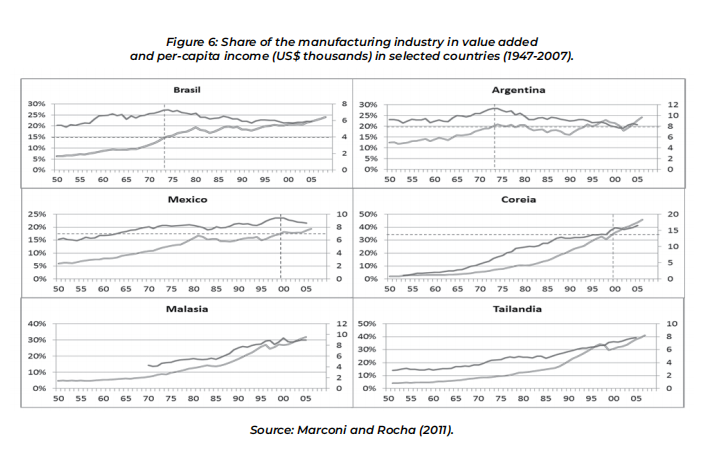

The data available for the Brazilian economy clearly show that the deindustrialization that occurred in Brazil is premature. As we can see in figure 6 below, the share of the manufacturing industry in the value added of the Brazilian economy began to reduce throughout the 1970s to a level of per-capita income of around US$ 4 thousand. Not only is this a value much lower than that observed in developed countries when they began their deindustrialization process, but also lower than that observed in other developing countries.

IS MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY A SECTOR LIKE ANY OTHER?

An argument that recurrently appears in the Brazilian debate on deindustrialization is that industry is a sector like any other, so that the reduction of its participation in employment and value added does not have major consequences for long-term growth. Thus, the increase in the importance of the service sector and primary activities in the Brazilian economy in recent years should not be seen as a source of concern for economic policymakers, as they do not signal a reduction in the growth potential of the Brazilian economy.

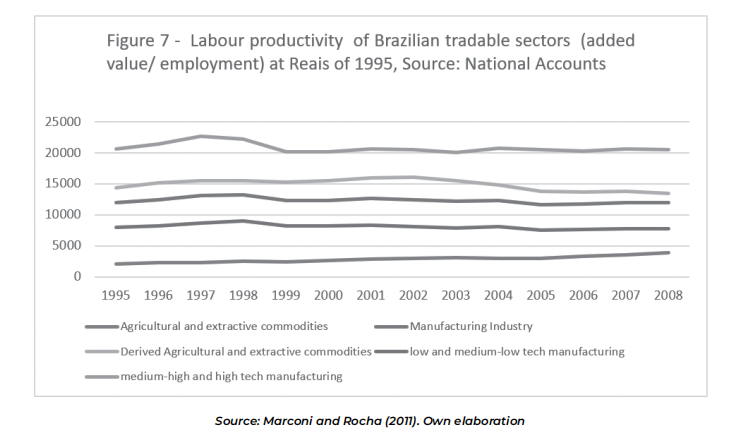

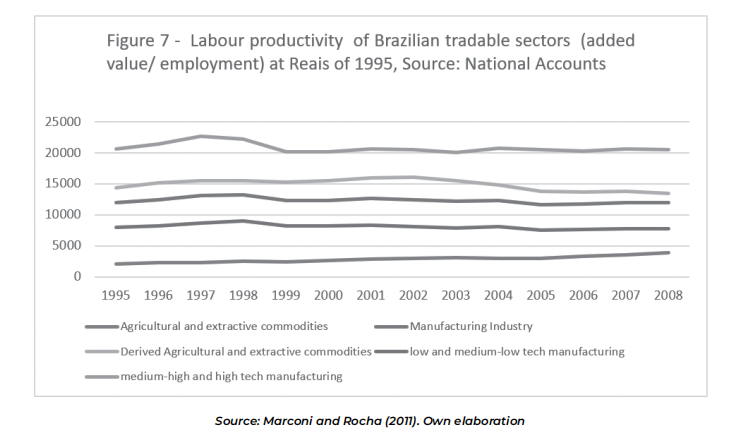

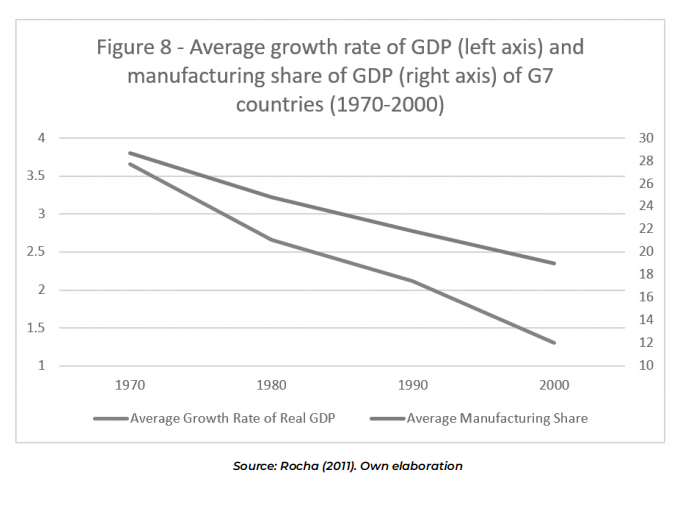

It is not true, however, that industry is a sector like any other. Indeed, when we look at the value-added/employment ratio – the relevant measure of productivity in a modern economy – we find that the value of this ratio for the manufacturing industry is approximately three times higher than that prevailing in the production of agricultural and extractive commodities (see Figure 7). This means that a reallocation of resources from the manufacturing industry to primary activities – a typical process of economies suffering from deindustrialization caused by Dutch disease – should produce a reduction in average labour productivity in the economy as a whole and, therefore, a reduction in per-capita income levels.

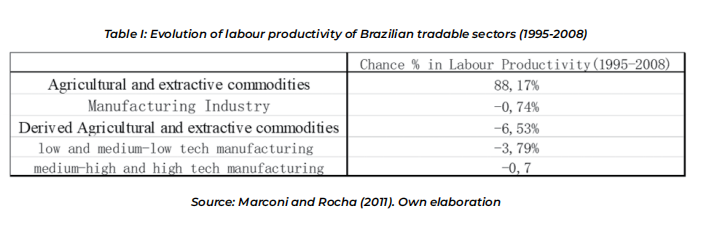

In Table I we can see the evolution of labour productivity in Brazilian tradable sectors in the period 1995-2008. Except for agricultural and extractive commodities that presented a remarkable growth of labour productivity during this period, the other tradeable sectors productivity stagnates or fall. This is particularly worrying for the low and medium-lo manufacturing sector, where cost advantages are of fundamental importance for international competitiveness. Labor productivity in the manufacturing industry remained stagnant in the period 1995-2008, because of the low investments made in the expansion/modernization of productive capacity (Oreiro et al, 2018). Moreover, the share of the employment in manufacturing industry on total employment remained unchanged in the period 1995-2008 because the manufacturing industry met the increase in sales with greater capacity utilization, but without making investments in the expansion/modernization of productive capacity. The manufacturing industry invested little in this period due to the combination of overvalued exchange rate/high real

interest rates.

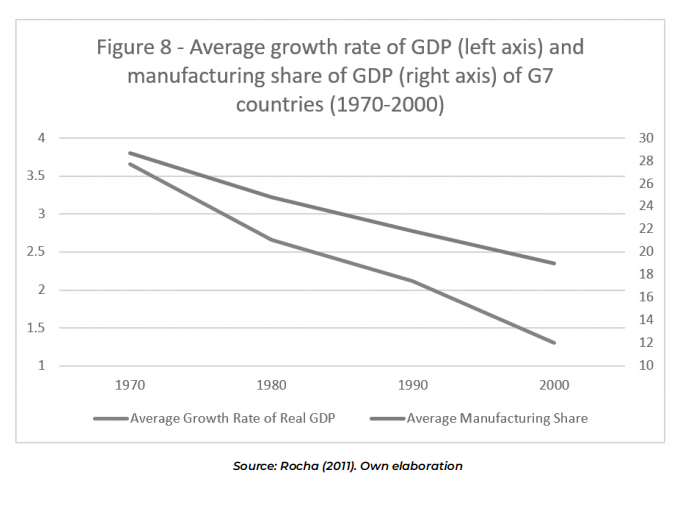

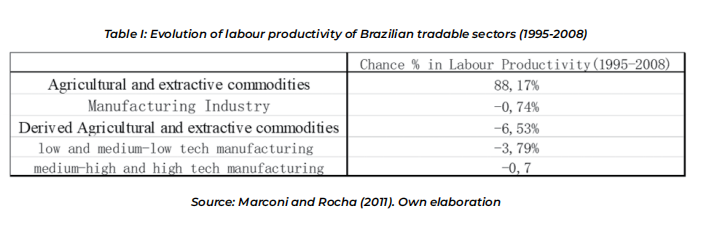

In addition, the data also seem to disprove the thesis that deindustrialization has no negative consequences over long-term growth. As show in Figure 8 below, the average growth rate of real GDP and the share of the manufacturing industry in the GDP of the G7 countries show a clear positive correlation in the period 1970-2000, where it can be seen that the observed reduction in the GDP growth rate of this group of countries was followed by a very significant reduction in the share of the manufacturing industry in the GDP of these economies.

ISN’T BRAZILIAN DEINDUSTRIALIZATION DUE TO THE APPRECIATION OF THE REAL EXCHANGE RATE?

This is perhaps the most widespread thesis among orthodox Brazilian economists. Currently, there are few who deny the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy, but they claim that it is not related to the strong appreciation of the exchange rate that has occurred since 2005 (See, for instance, Bacha, 2024).

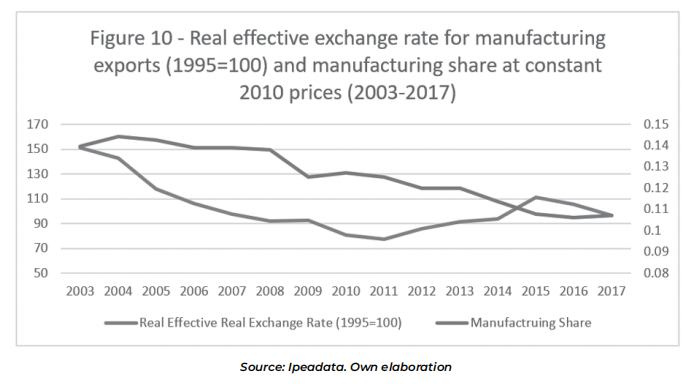

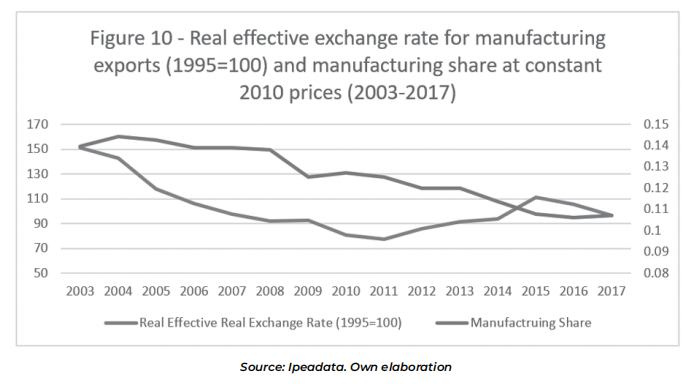

Once again, this thesis seems to be not very robust. When we compare the evolution of the real effective exchange rate for manufacturing exports and the share of the manufacturing industry in the GDP of the Brazilian economy in the period 2003-2017 (figure 10); we found that an appreciation of the real effective exchange rate of 36% in this period was followed by a drop in the share of the manufacturing industry in the GDP by 23%. It is clear to the naked eye that the strong appreciation of the real exchange rate is an important factor to explain the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy in this period.

Real exchange rate overvaluation, however, it is not the sole cause of Brazilian deindustrialization. As a matter of fact, the correlation between real effective real exchange rate is 0.42 for the period 2003-2017, which is positive but moderate. And correlation does not mean causality. Oreiro, D´agostini and Gala (2020) presented a new methodological procedure to decompose the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy in the period1997-2017 in the share that can be attributed to real exchange rate overvaluation and the share that can be attributed to the loss of non-price competitiveness of the Brazilian manufacturing industry due to the reducing economic complexity of Brazilian economy. To do that, the authors

calculated the so-called industrial equilibrium exchange rate for the Brazilian economy during the period 1998-2017, which is defined as the real exchange rate for which the manufacturing share should be constant through time. Once this industrial equilibrium rate was calculated then the authors calculated what should be the manufacturing share if the real exchange rate was kept at this industrial equilibrium level during the entire period. The authors show that only 38,94% of the deindustrialization over this period can be attributable to real exchange rate overvaluation, and 61,06% are due to loss of non-price competitiveness of Brazilian manufacturing share, that means due to increasing technological backwardness of

Brazilian manufacturing industry.

Still about the issue of the appreciation of the real exchange rate, a widespread thesis is that the appreciation of the real exchange rate observed in Brazil is similar to that of other emerging countries, which is why the relative competitiveness of the Brazilian industry would not have been affected by the behaviour of the exchange rate.

This thesis also does not correspond to the facts. In fact, as shown by Frenkel and Rapetti (2011), taking the year 2000 as the basis of the series, it is observed that the real exchange rate in Brazil was the one appreciated the most in a group of six Latin American economies in the period 2000-2010.

IS THE LOSS OF COMPETITIVENESS OF BRAZILIAN INDUSTRY DUE TO THE LOW DYNAMISM OF PRODUCTIVITY AND WAGE GROWTH?

This thesis is also widespread, even among heterodox economists. According to this thesis, Brazilian deindustrialization would be the result of the loss of competitiveness of the industry that results from the growth of wages above productivity, that is, from the increase in the unit cost of labour measured in national currency.

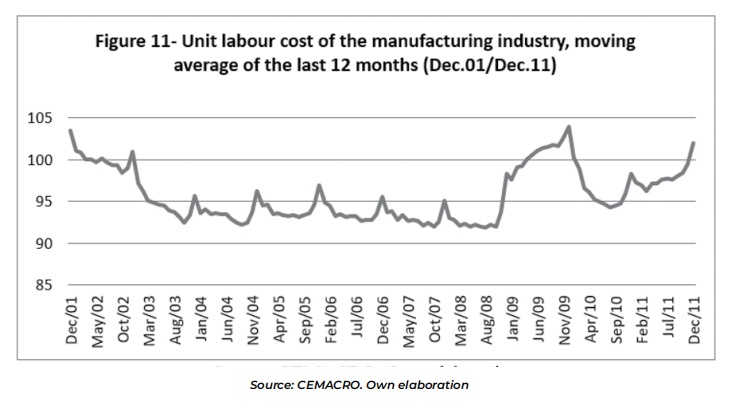

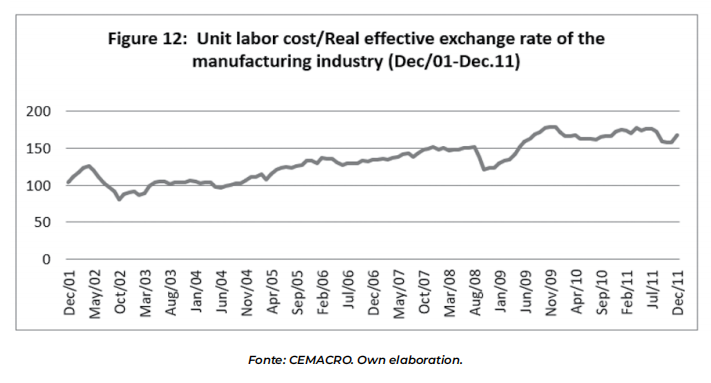

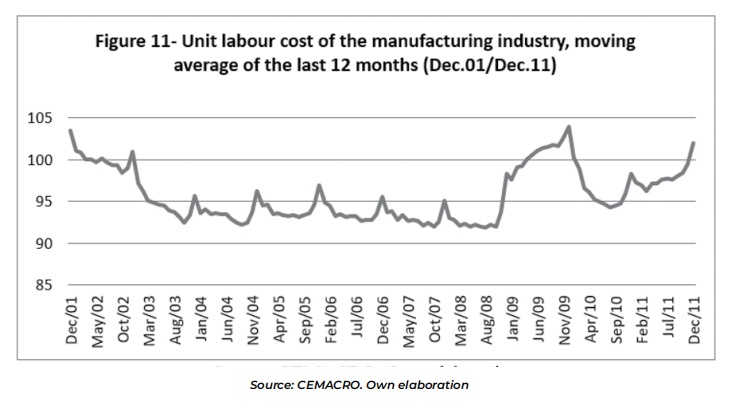

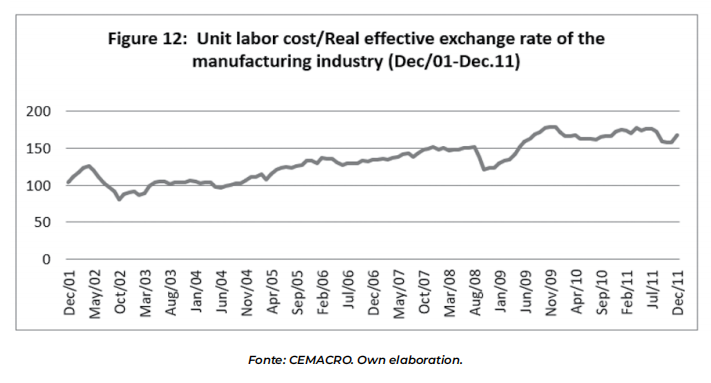

This thesis also does not adhere to the facts. In fact, when we look at the series of unit labour costs of the Brazilian manufacturing industry in the period between 12/2001 and 12/2011 (Figure 11), we do not find any upward trend in the variable in question. In fact, the prevailing index at the end of the period is like the prevailing at the beginning of the period. However, when we look at the unit labour cost/ real effective exchange rate series (Figure 12) we find that in the period under consideration it found an increase of about 60%. It follows that the fundamental reason for the loss of competitiveness of Brazilian industry is the appreciation of the real exchange rate, not the growth of wages above productivity.

IS THE EXCHANGE RATE APPRECIATION A RESULT OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE "SOCIAL WELFARE STATE"?

This thesis is based on the following reasoning. The implementation of the Social Welfare State in Brazil after the promulgation of the 1988 Constitution would have produced a perverse structure of incentives (broad social security coverage, unemployment insurance, etc.) that discourage intertemporal substitution of consumption and make the domestic savings rate in Brazil low. Thus, the macroeconomic balance between aggregate supply and demand requires a high real interest rate, which creates a large positive differential between the domestic

interest rate and the international interest rate. In an open economy with capital mobility, such as Brazil’s, this interest rate differential creates enormous incentives for the entry of speculative capital, which tends to appreciate the real exchange rate. In this way, the exchange rate appreciation and, consequently, the loss of competitiveness of the national industry, would be the by-product of the Brazilian Social Welfare State.

The premise that Brazil suffers from a problem of chronic scarcity of domestic savings due to the perverse incentives produced by the 1988 Constitution does not seem to be a plausible hypothesis. From the point of view of Keynesian theory, just as aggregate spending determines the overall income of the economy, aggregate savings result from business investment decisions. In fact, when we observe the behaviour of the investment rate and gross savings in Brazil between the 1st quarter of 2000 and the 1st quarter of 2011, we find that (i) the fluctuations of the savings rate are more intense than the fluctuations of the investment rate, but, roughly speaking, the fluctuations of the latter follow the fluctuations of the former, and (ii) the gross savings rate presents two moments of intense variation, namely, between the 1st quarter of 2003 and the 1st quarter of 2004, a period in which it presents a strong increase of 4%; and the 1st quarter of 2008 and the 1st quarter of 2009, a period in which the savings rate suffered a very significant reduction of 4.2%. These sudden changes in the gross savings rate cannot be attributed to changes in the welfare state, but rather to developments in the real exchange rate, the inflation rate, and the government’s tax policy. In fact, the beginning of the Lula government was characterized by the combination of a depreciated real exchange rate and a relatively high inflation rate (although declining), factors that combined depress real wages, thus producing a reduction in private consumption and, consequently, an increase in private domestic savings. Between 2008 and 2009, the reduction in the savings rate can be explained by temporary tax relief measures to stimulate the consumption of some durable goods to combat the effects of the global financial crisis. After the end of the temporary tax reduction programs, there was a significant recovery in the gross savings rate, which increased by 2.2% between the 1st quarter of 2009 and the 1st quarter of 2011.

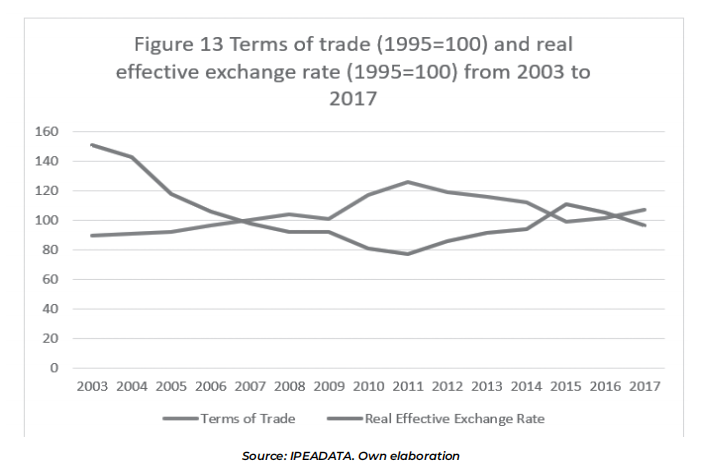

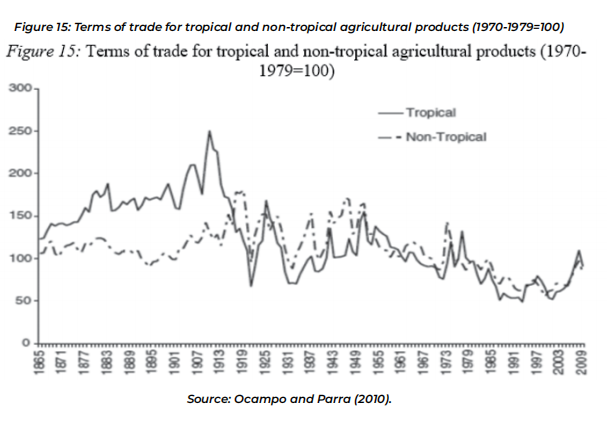

The behaviour of the real exchange rate in recent years seems to be more related to the recent dynamics of the terms of trade of the Brazilian economy. In fact, as shown in Figure 13 below, the terms of trade appreciated by 19,4% in the period between 2003 and 2017. In the same period, the real effective exchange rate appreciated by approximately 36%. Thus, the appreciation of the terms of trade, not the social policies of the Brazilian State, seems to be the main cause of the appreciation of the real exchange rate and, consequently, of the loss of competitiveness of the national industry.

IS THE EXCHANGE RATE APPRECIATION HERE TO STAY?

A final argument that is presented in the debates on the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy is that the exchange rate appreciation that has occurred in recent years is of a permanent nature – because of the appreciation of the terms of trade – so that the competitiveness of the Brazilian industry cannot be altered through changes in the exchange rate. Thus, the option would be to increase the productivity of the industry – probably by (sic) new rounds of trade opening – or to accept the continuity of the deindustrialization process.

It is not appropriate here to discuss the policies that could be used to reverse the exchange rate appreciation resulting from an improvement in the terms of trade11. We will limit ourselves to arguing that there are no grounds to affirm that the exchange rate appreciation experienced in recent years by the Brazilian economy is of a permanent nature.

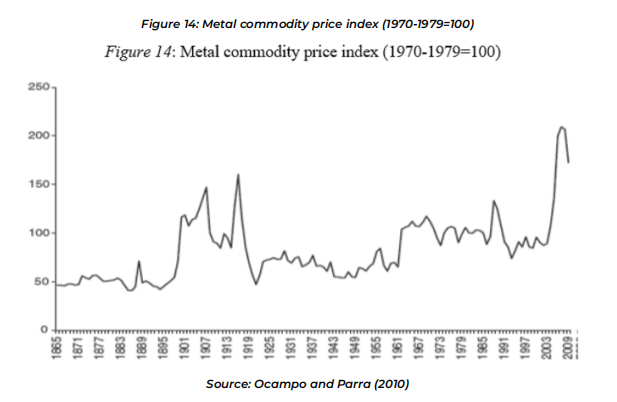

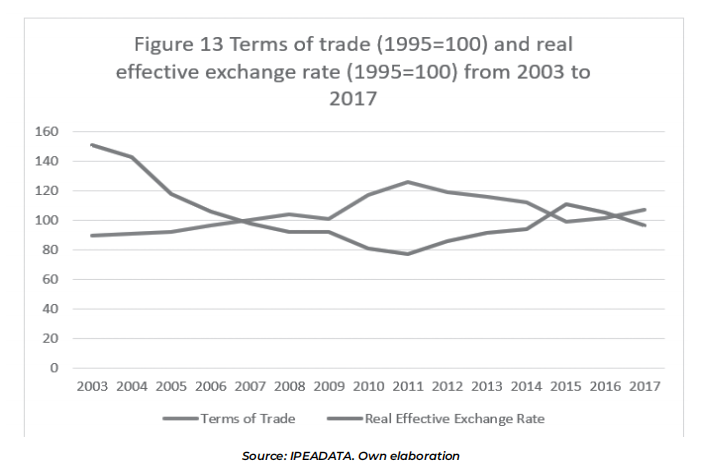

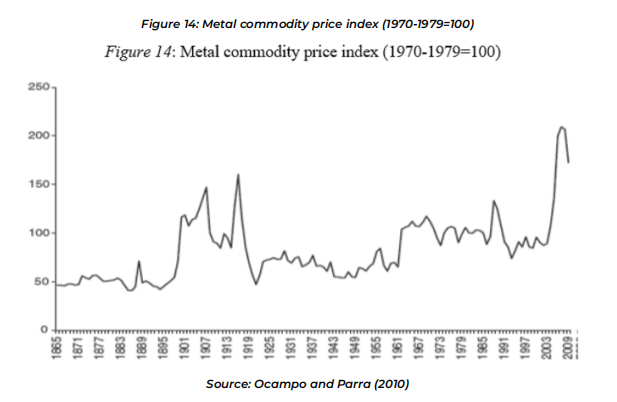

To do so, let us consider figures 14 and 15 below, which show the behaviour of the prices of metal commodities and tropical and non-tropical agricultural goods in the period 1865-2009. In the case of metal commodities, the recent behaviour of their prices is clearly atypical, being well above the historical average, which does not show any trend of increase or decrease over time. In the case of tropical and non-tropical agricultural goods, a clear downward trend in prices has been observed since the beginning of the twentieth century, which was partially interrupted at the beginning of the twenty-first century. This behaviour of the price of metal commodities and tropical and non-tropical agricultural products explains the improvement in the terms of trade observed in the Brazilian economy after 2003, thus being one of the reasons why the real exchange rate has shown a strong tendency to appreciation in recent years. But this situation is unlikely to last indefinitely. At some point, the price of metal commodities should return to the historical average and the prices of tropical and non-tropical agricultural

products should continue their downward trend. When this occurs, the terms of trade of the Brazilian economy should show a significant worsening, thus reversing the trend of appreciation of the real exchange rate.

11 In this regard, see Bresser-Pereira (2008) and Bresser-Pereira, Oreiro and Marconi (2015)

FINAL COMMENTS

Throughout this article we have made a critique of the various theses that orthodox economists present in the debate about the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy. Although these thesis are not necessarily compatible with each other, they present a common denominator, which is the idea that deindustrialization – if effective – would be a natural consequence of the development process of the Brazilian economy, that is, of the increase in the income elasticity of the demand for services that is induced by the growth of per-capita income; and aggravated by the low dynamism of labour productivity, resulting from the semi-autarkic nature of the Brazilian economy. In this context, real wages would tend to grow above labour productivity, thus increasing the unit cost of labour in national currency, which leads to a growing deterioration in the competitiveness of industry. The appreciation of

the real exchange rate observed since 2005 would be a secondary - that is, not a fundamental reason for the loss of competitiveness of the industry; but it would be related to the very logic of the Social Welfare State implanted de jure in Brazil, with the 1988 Constitution and, in fact, with the two terms of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Thus, the restoration of the competitiveness of industry through the devaluation of the exchange rate would be something unfeasible from the political point of view. Finally, it is argued that deindustrialization, even if irreversible, would not have negative effects on the growth potential of the Brazilian economy, because industry is a sector like any other, not being fundamental for a sustained increase in per-capita income in the medium and long term.

Contrary to these theses, we argue that:

1. The share of the Brazilian manufacturing industry in the GDP has been falling continuously since the mid-1970s, thus characterizing a clear process of deindustrialization.

2. In the last 10 years, deindustrialization has been accompanied by a re-primarization of the export agenda.

3. Brazilian deindustrialization is premature when compared to similar processes that occurred in developed countries, as it began at a level of per capita income much lower than that observed in developed countries when they began to deindustrialize.

4. There is strong evidence that Brazilian deindustrialization is strongly associated with exchange rate overvaluation.

5. The loss of competitiveness of the manufacturing industry in the period 2001- 2011 is mainly due to the overvaluation of the real exchange rate, although the growth of real wages ahead of labour productivity after 2008 has contributed to accelerate this process.

6. Labor productivity in the manufacturing industry remained stagnant in the period 1995-2008, because of the low investments made in the expansion/modernization of productive capacity.

7. The share of the manufacturing industry in total employment remained unchanged in the period 1995-2008 because the manufacturing industry met the increase in sales with greater capacity utilization, but without making investments in the expansion/modernization of productive capacity.

8. The manufacturing industry invested little in this period due to the combination of overvalued exchange rate/high real interest rates.

References

1. BACHA, E. (2024). “Por que a Indústria Brasileira Encolheu Tanto?”. Valor Econômico, 17 ofJully.

2. BONNELLI, R.; PESSOA, S. A. (2010). “Desindustrialização no Brasil: Um Resumo da Evidência”. FGV: Texto para Discussão n. 7.

3. BRESSER-PEREIRA, L.C (2008). “The Dutch Disease and Its Neutralization: a Ricardian Approach”, Revista de Economia Política, Vol. 28, N.1.

4. Bresser-Pereira, L. C., Oreiro, J. L.; Marconi, N. (2015). Developmental Macroeconomics: new developmentalism as a growth strategy. London: Routledge.

5. BRESSER-PEREIRA, L.C & MARCONI, N. (2008). “Existedoençaholandesa no Brasil?”. Papers andProceedingoftheIV Fórum de Economia de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio

Vargas: São Paulo

6. DUTT, A. K. (2003). “Income elasticities of imports, North-South trade and uneven development”. In: Development Economics and Structuralist Macroeconomics: Essays

in Honor of Lance Taylor. Amitava Krishna Dutt & Jaime Ros (Eds.). Edward Elgar: Alserhot.

7. FERREIRA, P.C; FRAGELLI, R. (2012). “Desindustrialização e ConflitoDistributivo”. Valor Econômico, 18 of April

8. Frenkel, R; Rapetti, M. (2011). “Fragilidad externa o desindustrialización: Cual es la principal amenaza de América Latina em la próximadécada?”. Working Paper, Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad (CEDES), Argentina.

9. MARCONI, N; ROCHA, M. (2011). “Desindustrializaçãoprecoce e sobrevalorização da taxa de câmbio”. Working Paper n.168, IPEA/DF.

10. MOREIRA, M. (1999). “A indústriabrasileiranosanos 90: o que jáfoifeito?” In: GIAMBIAGI, F.; MOREIRA, M. (Orgs.). A economiabrasileiranosanos 90. BNDES.

11. NASCIMENTO, L; OREIRO, J.L. (2024). “Industrial Policies for Reverting the Premature Deindustrialization of the Brazilian Economy: an agenda for policy discussion”. International Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 6, pp. 69-88.

12. NASSIF, A. (2008). “Háevidências de desindustrialização no Brasil?”. Revista de Economia Política. vol. 28, n.1 (109), pp. 72-96, January-March.

13. OCAMPO, JOSÉ ANTONIO; PARRA, MARIÁNGELA. (2010) “The terms of trade for Commodities since the MID-19th century”. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, vol 28, nº 1, p 11-43.

14. Oreiro J.L., D’Agostini, L.L., Gala P. (2020),” Deindustrialization, economic complexity and exchange rate overvaluation: the case of Brazil (1998-2017)”, PSL Quarterly Review,

73 (295):313 341.

15. Oreiro, J. L., D’Agostini, L. M., Vieira, F., Carvalho, L. (2018). “Revisiting Growth of Brazilian Economy (1980-2012)”. PSL Quarterly Review, 71(285), 203–229.

16. OREIRO, J.L & FEIJÓ, C. (2010). “Desindustrialização: conceituação, causas, efeitos e o casobrasileiro”. Revista de Economia Política, Vol.30, n.2.

17. Palma, J. G. (2005). Four sources of deindustrialization and a new concept of the Dutch disease. In J. A. Ocampo (Ed.), Beyond Reforms. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

18. PESSOA, S. (2011). “A EstabilizaçãoIncompleta”. Valor Econômico, 14 de June.

19. Rocha, I. (2011). “Some reflections about the economic development in Emerging Economies”. Working paper, Cambridge University, United Kingdom.

20. Rowthorn, R; RAMASWANY, R (1999). “Growth, Trade and Deindustrialization”. IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 46, N.1.

21. ROWTHORN, R.; WELLS, J. (1987). “Deindustrialization and foreign trade”. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

22. TREGENNA, F. (2009). “Characterizing deindustrialization: an analysis of changes in manufacturing employment and output internationally”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 33 (3) p. 433-466.

2. BONNELLI, R.; PESSOA, S. A. (2010). “Desindustrialização no Brasil: Um Resumo da Evidência”. FGV: Texto para Discussão n. 7.

3. BRESSER-PEREIRA, L.C (2008). “The Dutch Disease and Its Neutralization: a Ricardian Approach”, Revista de Economia Política, Vol. 28, N.1.

4. Bresser-Pereira, L. C., Oreiro, J. L.; Marconi, N. (2015). Developmental Macroeconomics: new developmentalism as a growth strategy. London: Routledge.

5. BRESSER-PEREIRA, L.C & MARCONI, N. (2008). “Existedoençaholandesa no Brasil?”. Papers andProceedingoftheIV Fórum de Economia de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio

Vargas: São Paulo

6. DUTT, A. K. (2003). “Income elasticities of imports, North-South trade and uneven development”. In: Development Economics and Structuralist Macroeconomics: Essays

in Honor of Lance Taylor. Amitava Krishna Dutt & Jaime Ros (Eds.). Edward Elgar: Alserhot.

7. FERREIRA, P.C; FRAGELLI, R. (2012). “Desindustrialização e ConflitoDistributivo”. Valor Econômico, 18 of April

8. Frenkel, R; Rapetti, M. (2011). “Fragilidad externa o desindustrialización: Cual es la principal amenaza de América Latina em la próximadécada?”. Working Paper, Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad (CEDES), Argentina.

9. MARCONI, N; ROCHA, M. (2011). “Desindustrializaçãoprecoce e sobrevalorização da taxa de câmbio”. Working Paper n.168, IPEA/DF.

10. MOREIRA, M. (1999). “A indústriabrasileiranosanos 90: o que jáfoifeito?” In: GIAMBIAGI, F.; MOREIRA, M. (Orgs.). A economiabrasileiranosanos 90. BNDES.

11. NASCIMENTO, L; OREIRO, J.L. (2024). “Industrial Policies for Reverting the Premature Deindustrialization of the Brazilian Economy: an agenda for policy discussion”. International Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 6, pp. 69-88.

12. NASSIF, A. (2008). “Háevidências de desindustrialização no Brasil?”. Revista de Economia Política. vol. 28, n.1 (109), pp. 72-96, January-March.

13. OCAMPO, JOSÉ ANTONIO; PARRA, MARIÁNGELA. (2010) “The terms of trade for Commodities since the MID-19th century”. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, vol 28, nº 1, p 11-43.

14. Oreiro J.L., D’Agostini, L.L., Gala P. (2020),” Deindustrialization, economic complexity and exchange rate overvaluation: the case of Brazil (1998-2017)”, PSL Quarterly Review,

73 (295):313 341.

15. Oreiro, J. L., D’Agostini, L. M., Vieira, F., Carvalho, L. (2018). “Revisiting Growth of Brazilian Economy (1980-2012)”. PSL Quarterly Review, 71(285), 203–229.

16. OREIRO, J.L & FEIJÓ, C. (2010). “Desindustrialização: conceituação, causas, efeitos e o casobrasileiro”. Revista de Economia Política, Vol.30, n.2.

17. Palma, J. G. (2005). Four sources of deindustrialization and a new concept of the Dutch disease. In J. A. Ocampo (Ed.), Beyond Reforms. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

18. PESSOA, S. (2011). “A EstabilizaçãoIncompleta”. Valor Econômico, 14 de June.

19. Rocha, I. (2011). “Some reflections about the economic development in Emerging Economies”. Working paper, Cambridge University, United Kingdom.

20. Rowthorn, R; RAMASWANY, R (1999). “Growth, Trade and Deindustrialization”. IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 46, N.1.

21. ROWTHORN, R.; WELLS, J. (1987). “Deindustrialization and foreign trade”. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

22. TREGENNA, F. (2009). “Characterizing deindustrialization: an analysis of changes in manufacturing employment and output internationally”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 33 (3) p. 433-466.

Published in

Volume 4, Issue 8, 2024

Keywords

DEINDUSTRIALIZATION

EXCHANGE RATE OVER - VALUATION

BRAZILIAN ECONOMY

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals